ACT IV: PART III

Moving on to other aspects of the ‘crash’ of Flight 93, we find that some early reports from the scene made mention of witness accounts of explosions and other unusual noises occurring before Flight 93 went down. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, for example, mentioned in passing that some witnesses “said they heard up to three loud booms before the jetliner went down.” (Jonathan D. Silver “Day of Terror: Outside Tiny Shanksville, a Fourth Deadly Stroke,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 12, 2001) One such witness was Laura Temyer, who told the Philadelphia Daily News that she “heard like a boom and the engine sounded funny … I heard two more booms – and then I did not hear anything.” Asked how she interpreted what she heard, she insisted that she believed “the plane was shot down.” Temyer has said that she has told her story twice to uninterested FBI officials. A number of other witnesses reported that “the engine seemed to race but then went eerily silent as the plane plummeted.” (William Bunch “Flight 93: We Know It Crashed, But Not Why,” Philadelphia Daily News, November 15, 2001)

Ernie Stull, the mayor of Shanksville, had some other interesting news to share with the Philadelphia Daily News: “’I know of two people – I will not mention names – that heard a missile … They both live very close, within a couple of hundred yards … this one fellow’s served in Vietnam and he says he’s heard them [before], and he heard one that day.” (William Bunch “Flight 93: We Know It Crashed, But Not Why,” Philadelphia Daily News, November 15, 2001) One such witness was Joe Wilt, who spoke to Ken Zapinski of the St. Petersburg Times: “The explosion unleashed a firestorm lasting five or 10 minutes and reaching several hundred yards into the sky, said Joe Wilt, 63, who lives a quarter mile from the crash site. ‘The first thing I thought it was was a missile,’ Wilt said.” (Ken Zapinski “A Blur in the Sky, Then a Firestorm,” St. Petersburg Times, September 12, 2001)

To briefly recap then what we have learned thus far:

· Although it is impossible to discern from any of the available photographs, and was impossible to discern even for those who were present at the scene in the immediate aftermath, United Airlines Flight 93 plowed into the ground near Shanksville, Pennsylvania.

· The aircraft was intact when it hit the ground, although area residents, the local press and local authorities were fooled into believing that the debris was spread over a swath of land more than eight miles long. (One early official estimate, provided by State Trooper Tom Spallone, amusingly claimed that the “debris field spread over an area [the] size of a football field, maybe two football fields.” In reality, the debris was deposited over an area the size of roughly 6,000 football fields. Including the end zones. [Cindi Lash and Ernie Hoffman “Crash in Somerset: ‘…Debris Field Spread Over an Area Size of a Football Field…’” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 11, 2001])

· Other than a C-130 flying high above, there were no military aircraft in the area before or after the crash, although a number of residents mistakenly thought they saw an unmarked white jet, and an air traffic controller mistakenly thought he tracked a military jet, and an earthquake monitoring station erroneously recorded the presence of a military jet, and a number of residents falsely reported that a plane capable of high speed flight at extremely low altitudes passed over their homes.

· There were no explosions on the plane before it went down, although numerous witnesses who had apparently ingested some powerful hallucinogens claimed that burning debris came raining down from the sky, that clouds of debris settled over the Indian Lake area, that there were multiple explosions heard before the crash, and that a missile was heard in the vicinity of the crash.

Speaking of pre-crash explosions, we do have one other key witness, albeit one mired in controversy within the 9-11 skeptics club. That witness was Edward Felt, listed as a passenger on the doomed flight. As reported by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and other media outlets before the story was scrubbed, Mr. Felt placed a rather infamous call from the aircraft at approximately 9:58 AM, about eight minutes before the time of the alleged crash: “a telling detail came minutes before the plane went down when dispatchers at the Westmoreland County Emergency Operations Center intercepted a frantic cell phone call made to 911 by a passenger aboard the doomed flight. ‘We are being hijacked, we are being hijacked!’ the man told dispatchers in a quivering voice during a conversation that lasted about one minute. ‘We got the call about 9:58 this morning from a male passenger stating that he was locked in the bathroom of United Flight 93 traveling from Newark to San Francisco, and they were being hijacked,’ said Glenn Cramer, a 911 supervisor. ‘We confirmed that with him several times and we asked him to repeat what he said. He was very distraught. He said he believed the plane was going down. He did hear some sort of an explosion and saw white smoke coming from the plane, but he didn’t know where. And then we lost contact with him.'” (Jonathan D. Silver “Day of Terror: Outside Tiny Shanksville, a Fourth Deadly Stroke,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 12, 2001)

As many readers are no doubt aware, there has been considerable debate within the 9-11 skeptics’ community over the legitimacy of the phone calls reportedly placed from the hijacked planes, particularly in the case of Flight 93. While many, if not most, skeptics seem to favor the belief that it would have been impossible for the calls to be placed, I’m afraid I must here part company with my fellow skeptics – which I am sure will come as quite a shock to readers familiar with my past writings.

According to various media reports from publications around the country, all of the following calls were placed by passengers and crew aboard Flight 93: Passenger Jeremy Glick spoke very briefly to his mother-in-law, JoAnne Makely, and then to his wife, Lyzbeth; passenger Lauren Grandcolas called and left a message for her husband, Jack; passenger Honor Elizabeth Wainio called her step-mother, Esther Heymann; flight attendant CeeCee Lyles twice called for her husband, Lorne, the first time reaching an answering machine; passenger Mark Bingham talked first to his aunt, Kathy Hoglan, and then to his mother, Alice Hoglan; passenger Linda Gronlund called her sister, Elsa Strong; passenger Joe DeLuca called his father, Joseph, Sr.; passenger Tom Burnett called his wife, Deena (four times); passenger Andrew Garcia called his wife, Dorothy; passenger Marion Britton called her good friend, Fred Fiumano; flight attendant Sandra Bradshaw called her husband, Phil; passenger Louis Nacke called his wife, Amy; passenger Todd Beamer spoke at length to GTE Airphone supervisor Lisa Jefferson; and passenger Edward Felt called 9-11 operator Glen Cramer to report an explosion and smoke aboard the aircraft.

All of these calls were reportedly placed between about 9:20 AM, when passengers first realized that the aircraft had been hijacked, and 9:58 AM, when Todd Beamer purportedly ended his call to Lisa Jefferson with the immortal words, “Let’s roll,” and Ed Felt frantically placed a 9-11 call that was abruptly terminated. Eight minutes later, the plane purportedly slammed into the ground.

The phone calls, as recounted by the recipients, were remarkably consistent in describing the situation that the passengers and crew were facing: the distressed callers spoke of three men, all in red bandannas and all Middle-Eastern in appearance, who had commandeered the aircraft. Two of the men had entered the cockpit and presumably taken control of the plane. The third, sporting what was undoubtedly a fake bomb around his waist, was standing guard over the first class passengers. The thirty or so coach passengers, huddled in the back of the plane along with the flight crew, were left unguarded, thus explaining how they were all able to use telephones during the ordeal. Two individuals, either first class passengers or members of the flight crew, had been stabbed and lay dead or dying in the first class cabin. A number of passengers and crew members, some probably unaware that other passengers were sharing similar thoughts, spoke of taking action against the outnumbered hijackers.

So goes the story as reportedly told by the passengers of Flight 93. And so goes the story as well as told by our fearless leaders in Washington, at least up until the point that the passenger revolt began. And therein lies the problem, for the story told by the passengers, in conforming too closely to the government’s version of events, poses problems for some of the alternative theories that have arisen to explain the events of September 11 – in particular, the theory that claims that there were no actual hijackers and that the planes were commandeered via remote control, and the theory that claims that there weren’t actually any planes used that day and that the entire production was nothing but a Hollywood special effects show.

Since numerous people in the skeptic’s movement have warmly embraced one or the other of these two theories, many of these same people have expended a considerable amount of energy attempting to ‘debunk’ the phone calls. Unfortunately, in doing so they have made various claims that are themselves, alas, fairly easily debunked.

For example, it has been claimed that the aluminum skin of a commercial aircraft acts as a shield of sorts that prevents or severely restricts the transmission of cell phone calls. This claim is belied by the fact that thousands of cell phone calls are successfully placed every day from aircraft sitting on the tarmac at airports around the world. It has also been claimed that, since cell phone reception is not very good even on the ground in the area around Shanksville, it is preposterous to suggest that it would be possible to get a cell phone signal in an airplane above Shanksville. This argument, however, ignores the fact that none of the calls would have been placed when the plane was anywhere near Shanksville. During the time that the calls were reportedly made, Flight 93 would have been passing over or very near a series of reasonably large population centers: Cleveland, Akron and Youngstown, Ohio, followed by Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. If Flight 93 came to an end in Shanksville at 10:06 AM, and if it had been traveling at roughly 500 miles per hour, then it was still about 65 miles outside of Shanksville when the last calls were placed.

Probably the most commonly encountered dubious claim concerning the phone calls is one that is sometimes stated explicitly and sometimes just implied: that all the calls reportedly placed from Flight 93 were made with cell phones. The reality, however, is that the majority of the calls appear to have been placed using fairly reliable, though rather expensive, seatback Airphones. And before you write me angry letters, let me save you the trouble, because I already know what you are going to say; it goes a little something like this: “at first, they tried to say that all the calls were made using cell phones, but then after all us skeptics started pointing out that the cell phone calls would have been (either very unlikely or impossible, depending upon who is telling the story), then they changed the story and started saying that the calls were made on Airphones.”

That claim, as it turns out, is also rather easily debunked. On September 30, 2001, less than three weeks after the attacks, the Chicago Tribune published the following report: “In the cabin, passengers frantically began making calls, 23 from the seat-back phones alone from 9:31 to 9:52 a.m. Others passed cell phones to people who had been strangers just minutes before.” (Kim Barker, Louise Kiernan and Steve Mills “Heroes Stand Up Even in the Hour of Their Deaths,” Chicago Tribune, September 30, 2001) The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette had already said much the same thing a week and a half earlier when it was noted that Todd Beamer’s call “was one of nearly two dozen in-flight calls from Flight 93 between 9 and 10 a.m. EDT that day.” (Jim McKinnon “GTE Operator Connects With, Uplifts Widow of Hero in Hijacking,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 19, 2001) Even earlier than that, within just a day or two of the attacks, it had been reported that Mark Bingham called his mother “from the air phone in the seat in front of him,” and that Jeremy Glick “got on a seat phone to his wife, Lyzbeth.” (Jaxon Van Derbeken “Bay Area Man’s Last Seconds of Bravery,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 12, 2001 and Stacy Finz, Jaxon Van Derbeken and Sam McManis “Passengers on S.F. Flight Died Heroes,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 13, 2001)

I am not arguing here, by the way, that because it was reported in the mainstream press that the calls were placed via Airphones that it must necessarily be true. What is at issue here is whether the reports, regardless of their veracity, preceded the claims by skeptics that the calls would have been impossible. And since the reports clearly came before the claims of skeptics, there appears to be no merit to the charge that Washington and the media changed the official story in response to skepticism over the phone calls.

It is impossible to know how many cell phone calls were placed to supplement the Airphone calls. What we do know is that many of the reported calls were very brief, with more than a few ending abruptly. Andrew Garcia, for example, was only able to get out his wife’s name, “Dorothy,” before the connection was lost. It seems reasonable to assume that calls such as Garcia’s were the most likely ones to have been placed via cell phones. And we know for certain that Edward Felt’s call, which was dropped prematurely, had to have been made by cell phone since he indicated that he was calling from a restroom, well beyond the reach of an Airphone.

Taking all this into consideration, the first question that comes to mind is: what would have been achieved by faking the cell phone calls? If the storyline was firmly established by the Airphone calls, particularly Jeremy Glick’s detailed 20-30 minute call to his wife, Lyzbeth, and Todd Beamer’s 13-15 minute call to Lisa Jefferson, then why bother with adding redundant cell phone calls that would be vulnerable to detection as fakes? The second question that comes to mind is: if the plan was to fabricate cell phone calls, why go to the trouble of manufacturing calls such as Garcia’s, which did nothing to advance or promote the storyline? And why fake Felt’s frantic call, which directly contradicted a key element of the official storyline?

If the cell phone calls were faked, doesn’t it seem a little odd that the one call that could only have been made from a cell phone, Edward Felt’s call from the restroom, is the one that the government would prefer that you not know about? (The FBI reportedly seized the audiotape of the call, and the operator who fielded it, Glen Cramer, “received orders not to speak to the media.” [John Carlin “Unanswered Questions: The Mystery of Flight 93,” The Independent, August 13, 2002]) And doesn’t it also seem a little odd that during all of the supposedly fake, scripted calls, “none of the callers mentioned a fourth hijacker,” despite the fact that the official story features not three but four hijackers? (Kim Barker, Louise Kiernan and Steve Mills “Heroes Stand Up Even in the Hour of Their Deaths,” Chicago Tribune, September 30, 2001)

By most accounts, successfully placing a cell phone call from a moving aircraft was not an easy thing to do with the technology available in 2001. The problem apparently stems from the fact that an airplane quite obviously moves very fast, thus passing through reception ‘cells’ very quickly. It is extremely difficult, therefore, to get and maintain a cell phone signal. It is not, however, impossible.

Imagine that you are trapped on a speeding airplane that has been hijacked and you know that, short of some kind of miracle, you are living the last minutes of your life. Imagine also that you have a cell phone at your disposal, but you realize that it is very unlikely to work. During the last, say, forty-five minutes of your life, what do you think you would spend most of your time doing? I am going to take a wild guess here and say that most people in that situation would spend a considerable amount of time frantically punching the numbers of loved ones into their cell phones and hitting the “send” button. Repeatedly. And I’m also guessing that, given the ubiquity of cell phones these days, there were more than a few of them, from various service providers, available to passengers and crew members that day. So it is probably safe to say, without exaggeration, that literally hundreds of cell phone calls were attempted during the final forty-five minutes of Flight 93. And even if the calls had, say, a 98% failure rate, we might reasonably expect a handful of them to get through, if only long enough to say a few final words.

The real issue here though, it appears to me, is not whether the calls were technologically possible. That seems to be almost a moot point. As previously stated, the cell phone calls added nothing to the narrative established by the Airphone calls, and no one has argued, as far as I know, that Airphones don’t really work. If that were the case, you would think there would have been some complaints over the years from all the people who have coughed up $7+ per minute to use them. So the real question we need to ask here is: were all the calls, regardless of how they were reportedly placed, manufactured – presumably to create a patriotic, uplifting storyline?

There appear to be three primary theories concerning the purportedly faked phone calls. It is not really for me to say which is the most absurd and/or offensive, but I probably will do so anyway as we proceed along.

The first theory holds that there were no actual airplanes used, and hence no actual passengers, crew members or hijackers. And if there were no airplanes or passengers, then obviously there couldn’t possibly have been any phone calls placed. How then were they faked? Easy enough – they were created out of thin air by the scriptwriters who wrote the screenplay for the day’s events. According to this theory, the passenger lists were faked and there were no real passengers, so there obviously could not have been any real surviving family members either. In other words, all the people involved in the phone calls, both callers and recipients, never really existed at all. It was all just made up.

If this theory is incorrect and there were real victims aboard Flight 93, with real grieving family members, then it is difficult to imagine how offensive such a theory would be to those surviving family members. We would assume, therefore, that any researcher promoting such a theory would have carefully done their homework before offering up a scenario that could seriously hamper efforts to gain a wider audience for alternative 9-11 theories.

After all, it would not have been that difficult a task. They could have begun by reading through the profiles of each passenger and crew member published by the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette back in October 2001. There they would have found photographs of and biographical information about each fake passenger – specific information that can be checked for authenticity, like family, educational and employment histories, and names of surviving family members. With that information in hand, one could then do a little sleuthing to determine, for example, whether the purportedly fake family members really do exist.

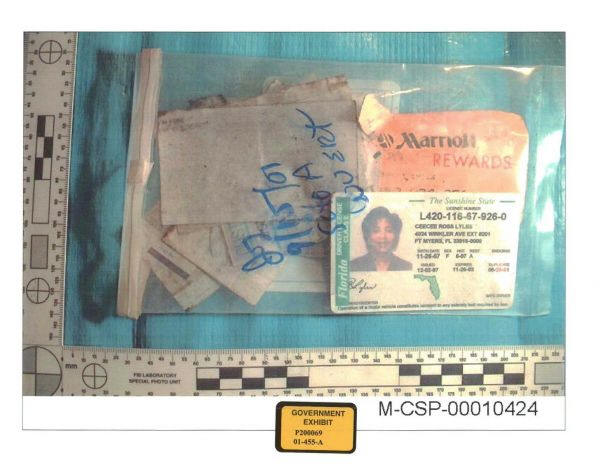

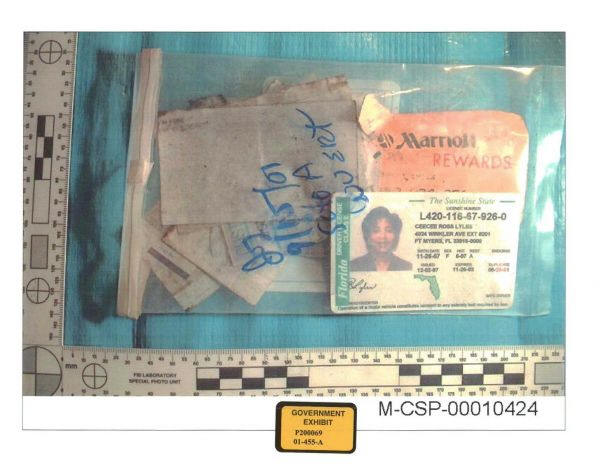

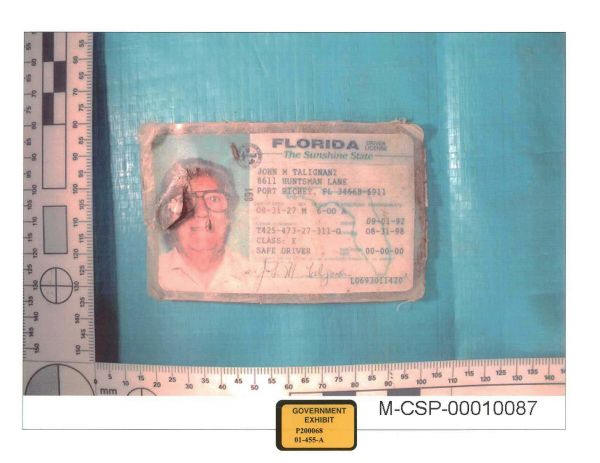

This really isn’t fucking rocket science, people. It doesn’t take much time or technical expertise to discover, for example, that a Reverend Paul Britton, fake surviving brother of fake Flight 93 passenger Marion Britton, still lives and works in the fake town of Huntington Station, New York; or to find that Lorne Lyles, fake husband of fake flight attendant CeeCee Lyles, now lives in the fake city of Gibsonton, Florida, about fifty miles north of the fake address shown on his fake deceased wife’s fake drivers license, which also contains a fake photo, fake drivers license number, and fake physical description – as does, come to think of it, the fake drivers license of fake passenger John Talignani, whose fake stepson, Mitchell Zykofsky (pictured below alone and with his fake brothers and fake stepfather), is still a fake NYPD detective.

It is possible, of course, that all the grieving relatives (including the fake Beaven brothers pictured to the lower right, grieving over the loss of their fake dad) who descended upon Shanksville to attend memorial services were all actors. And it is possible that all the grieving relatives who went on radio and television to discuss their losses and, in some cases, the fake phone calls they received, were actors as well. It is even possible that to this day, five years after the fact, they are still dutifully playing their parts (although at least one of them –

Melodie Homer, fake widow of fake co-pilot Leroy Homer – seems to have lost her copy of the script). It is also possible that reporters from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette – some of the very same reporters, notably, who were all but alone in reporting on such anomalies as the mysterious white jet, the eight-mile debris trail, the pre-crash explosions, and the lack of identifiable aircraft wreckage at the alleged crash site – decided to toe the government line by fabricating richly textured fake lives and fake careers for all the fake passengers and fake crew members aboard fake Flight 93. Or maybe the reporters were just fooled by the legions of actors the government had in place ready to supply fake anecdotes about their fake deceased relatives.

In this day and age, virtually anything is possible, I suppose. But is it at all probable? And has anyone made any attempt to put together a credible case in support of such a scenario, or have they just tossed it out there because they had already firmly hitched their wagons to a dubious theory that they must now force all the available evidence to comply with? As far as I can see, the latter appears to be the case.

Using a standard ten-point rating system, I am going to have to give this theory an 8 on the Offensiveness Scale and about a 7 on the Absurdity Scale.

Yet another contender in the dubious theory competition is the one that claims that the passengers were real, as were the relatives who received real telephone calls, but those calls, you see, were not actually placed by the passengers, although the various relatives were all fooled into believing that they were. How was it done? It’s a rather complicated scenario, but basically it boils down to this: a special ‘war room’ of sorts was set up, staffed by a group of operatives employing special voice mimicking software that allowed them to assume the vocal identities, as it were, of all the passengers and crew members. In this war room, a movie of the scripted event was played, complete with sound effects and appropriate background noise. This allowed all the operatives to be on the same page, so to speak, as they made their calls, relaying information that was actually transpiring in the movie, not on the actual plane, although the movie was perfectly synchronized with the actual movements and flight pattern of Flight 93. Or something like that. Prior to perpetrating this hoax, of course, the conspirators had to obtain, by various cloak and dagger means, samples of all the voices that they planned to mimic. And they had to learn enough about their forty subjects to know, for example, the names of spouses, parents, children and other loved ones. And they had to learn how their subjects responded to highly stressful situations, so that they could accurately portray them in such a situation. And, perhaps most importantly, they had to learn to communicate in that kind of private language that all intimate couples develop over time, so that they would be able to fool husbands and wives, as well as parents and siblings – so that they could not only speak in the proper voice, but also use the right words and phrases.

How were they able to pull this off? Beats the hell out of me. All that I can say is that, while I am aware that the primary proponent of this theory, A.K. Dewdney, appears to be fairly well respected within the 9-11 skeptics community, I am going to have to give his theory a solid 9 on the Absurdity Scale, along with a 7 on the Offensiveness Scale. The only reason I am not awarding it a perfect 10 is that there is a slight possibility that someone out there might propose something even more ludicrous. For those who would like a more detailed explanation of this theory, drop by

www.physics911.net/cellphoneflight93.htm, or run a Google search to find some of Dewdney’s other screeds.

Yet another theory that I stumbled upon while researching this series of posts posits that the surviving relatives of the passengers of Flight 93 are quite real, but they did not receive the phone calls that they claim to have received. They are, you see, co-conspirators of sorts in that they are willingly lying at the behest of the government to help perpetrate this hoax. According to this theory, the victims didn’t actually die on Flight 93, but rather died either before September 11 or during the attacks on the World Trade Center. Nevertheless, all the families went along with the ruse to help manufacture a great story about average Americans as heroes. Why? Because, uhmm, all the surviving family members are covert operatives? … or because they were all paid handsomely for their complicity? … or, uhhm, actually, I don’t really know; I didn’t spend enough time with this particular theory to weed out all the fine details. Let’s just award it a 9 on both the Absurdity and Offensiveness Scales and move on.

One thing that becomes clear while wading through all these theories is that a considerable amount of time has been devoted to attempts at ‘debunking’ the Flight 93 phone calls. There appears to be little doubt, however, that the surviving relatives of the passengers and crew members of Flight 93 – like Gordon Felt, to the left, brother of Edward Felt – are real people who lost a loved one on September 11, 2001. And it appears as though they honestly believe that they received phone calls from those loved ones as the final minutes of their lives played out on that doomed airliner. There is no indication, on the other hand, that they didn’t know their husbands and wives and sons and daughters well enough to know whether they were talking to real people or a team of electronic Rich Littles. And there is no reason to believe that surviving relatives such as Jerry and Beatrice Guadagno were complicit in covering up the cause of death of their only son, Richard.

However … there are clear indications that the most widely publicized call – the keynote call as it were, the legendary Todd Beamer “Let’s Roll” call – was fabricated. With the exception of Ed Felt’s call reporting an explosion on board, Beamer’s was the only call placed to someone other than a family member or close friend. The operator who allegedly fielded the call, Lisa Jefferson, knew nothing about the man she allegedly spoke with and prayed with. While most of the other calls from Flight 93 were quite brief, Beamer purportedly remained on the line for at least 13 minutes (15 by some accounts), and yet he inexplicably never asked to be connected to his wife or other loved ones, choosing instead, in the final minutes of his life, to carry on an extended dialogue with a complete stranger.

Lisa Beamer did not learn of her husband’s alleged call until four days later, after which she was allowed to speak with Ms. Jefferson, who had been, I’m guessing, suitably prepped. The FBI had purportedly been keeping the Beamer call under wraps until the information allegedly revealed therein could be reviewed and cleared for release. To this day, it appears as though no one has heard a tape of the call or even seen a transcript. Lisa Beamer was provided only with what was described as a “summary” of the call.

Curiously, Todd Beamer’s boss appears to have learned of the “Todd Beamer as America hero” storyline before Lisa Beamer did, even though Lisa was supposedly the first civilian informed of the infamous phone call. (Rowland Morgan “Flight 93 ‘Was Shot Down’ Claims Book,” Daily Mail, August 18, 2006) Even more curiously, Todd Beamer’s boss happens to be an executive at the Oracle Corp., whose early history can be found on the company’s website: “Larry Ellison and Bob Miner were working on a consulting project for the CIA (Central Intelligence Agency in USA) where the CIA wanted to use this new SQL language that IBM had written a white paper about. The code name for the project was Oracle (the CIA saw this as the system to give all answers to all questions or something such ;-). The project eventually died (of sorts) but Larry and Bob saw the opportunity to take what they had started and market it. So they used that project’s codename of Oracle to name their new RDBMS engine. Funny thing is, that one of Oracle’s first customers was the CIA…” (

http://www.orafaq.com/)

Another funny thing is, that the Oracle Corp. is what is commonly referred to as a CIA ‘front’ company. But one that is, at least, rather candid and cheerful about it.

What then are we to make of Todd Beamer’s undocumented phone call? If for no other reason than that Beamer did not use any of his 13 minutes of airtime to speak to his wife or another family member, the call seems suspect. Less than a week after Flight 93 went down, it was reported that, during the time that calls were placed from the aircraft, “the phone rang twice [at the Beamer home], stopped, then moments later, rang once more. ‘When I picked it up, it was dead air,’ Lisa Beamer said. ‘I feel fairly confident that it was Todd. It would be on his mind to call me, to protect me.’” (Jaxon Van Derbeken “Bound By Fate, Determination: The Final Hours of the Passengers Aboard S.F.-Bound Flight 93,” San Francisco Chronicle, September 17, 2001)

One would think that it would indeed be on Todd Beamer’s mind to call and, if nothing else, say goodbye to his wife and kids. But how could he have attempted to do that if he was allegedly already on the phone carrying on a lengthy conversation with Lisa Jefferson? Did he try to call his wife before calling Jefferson? If so, then why did he suddenly lose interest in speaking to her after he got an operator on the line? Did he try to call his wife after speaking to Jefferson? If so, then why did he terminate the secure connection that he already had rather than just having his call transferred? That is, after all, the kind of thing that telephone operators specialize in.

Was Lisa [Jefferson] fooled by someone posing as Todd Beamer? Or was there ever a call placed at all by someone claiming to be Todd Beamer? Could the alleged call have been entirely fabricated after the fact, during the four days before Lisa Beamer received notification and the story hit the press? And if so, then why? Other than adding the “Let’s Roll” tagline for the ‘War on Terrorism,’ Beamer’s call added little to the storyline established through the other calls, which do not appear to have been faked.

Such are the mysteries still surrounding United Airlines Flight 93. In the next installment, we will review some of the most popular conspiracy theories concerning the fate of United Airlines Flight 93, and, in doing so, possibly find some answers to some of the lingering questions surrounding the ‘flight that fought back.’

Looks like this should be titled “Part II”, while the next entry should be titled “Part III”.

I’m not sure what you mean. It looks correct to me, but I’m not sure if I’m looking at the wrong place. Can you help me identify where this error is?

Lisa Jefferson’s name is given as Lisa Jackson in the second-to-last paragraph.

Thanks! I’ve made that correction.