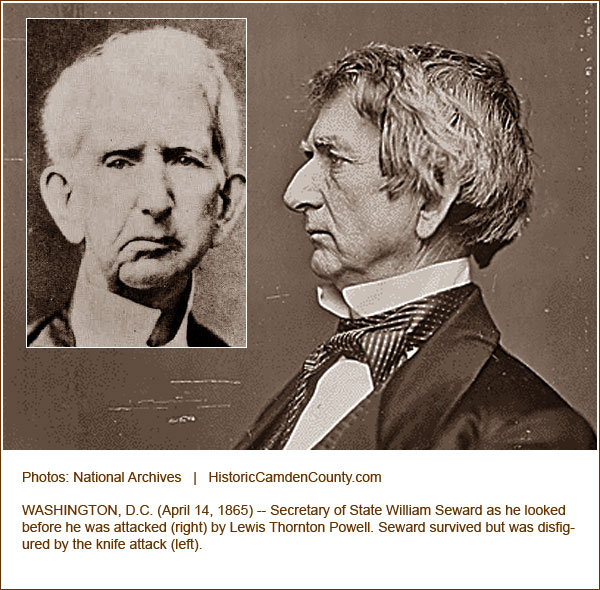

In my continuing quest to gain some kind of understanding of exactly what happened on the night of April 14, 1865, I have worked my way through several more rather tedious treatments of the Lincoln assassination, including a relatively new tome by Leonard Guttridge and Ray Neff (Dark Union, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2003) that adds several new layers of complexity to the fabled attack on Secretary of State William Seward. And by “new layers of complexity,” I really mean new layers of absurdity.

One thing we learn from the authors is that the “house where the Sewards lived was a thirty-room mansion overlooking Lafayette Square.” A three-story, thirty-room mansion. But like virtually everyone else who has written about the alleged attack at the Seward home, the authors offer little commentary on how Lewis Powell, who by all accounts had never been in the home, could have so easily navigated his way through it.

The authors also inform us that, “This was no assassin’s work. Seward’s body was otherwise unscathed. The knife struck nowhere near the heart or any other vital organ. It was not aimed at the windpipe. It targeted Seward’s face – in particular, his ligatured jaw.” In other words, none of the wounds that Seward allegedly sustained that night were inconsistent with the injuries he was known to have suffered as a result of the carriage accident. It is, I have to say, a rather remarkable ‘coincidence’ that Powell’s knife struck only where Seward was previously injured.

Contradicting virtually everything else that has been written about the alleged attempted assassination of Seward, Guttridge and Neff also claim that “Two male nurses had been assigned to the secretary, and two State Department messengers, each armed with a Colt revolver, were working shifts as Seward’s bodyguard. That Good Friday evening one of the messengers, Emerick Hansell, reached Seward’s home shortly after nine in the evening … After a meal in the kitchen, he settled himself in an alcove on the third floor, where most of the family bedrooms were located.”

So now we find that, in addition to two active-duty military personnel (George Robinson and Augustus Seward) and two other able-bodied men (William Bell and Frederick Seward) being present in the home, William Seward actually had an armed guard stationed right down the hall from his room – and yet Powell was still able to locate, get to, and brutally attack his target. Well done, Mr. Powell!

According to Guttridge and Neff, Hansell didn’t enter into the melee until after William Seward had been attacked and Powell was grappling with Robinson: “Then another figure plunged into the room. It wasn’t Fred. He had already staggered to his bedroom, beaten nearly senseless. The new arrival was Emerick Hansell … He heard Robinson cry, ‘Hansey, help me.’”

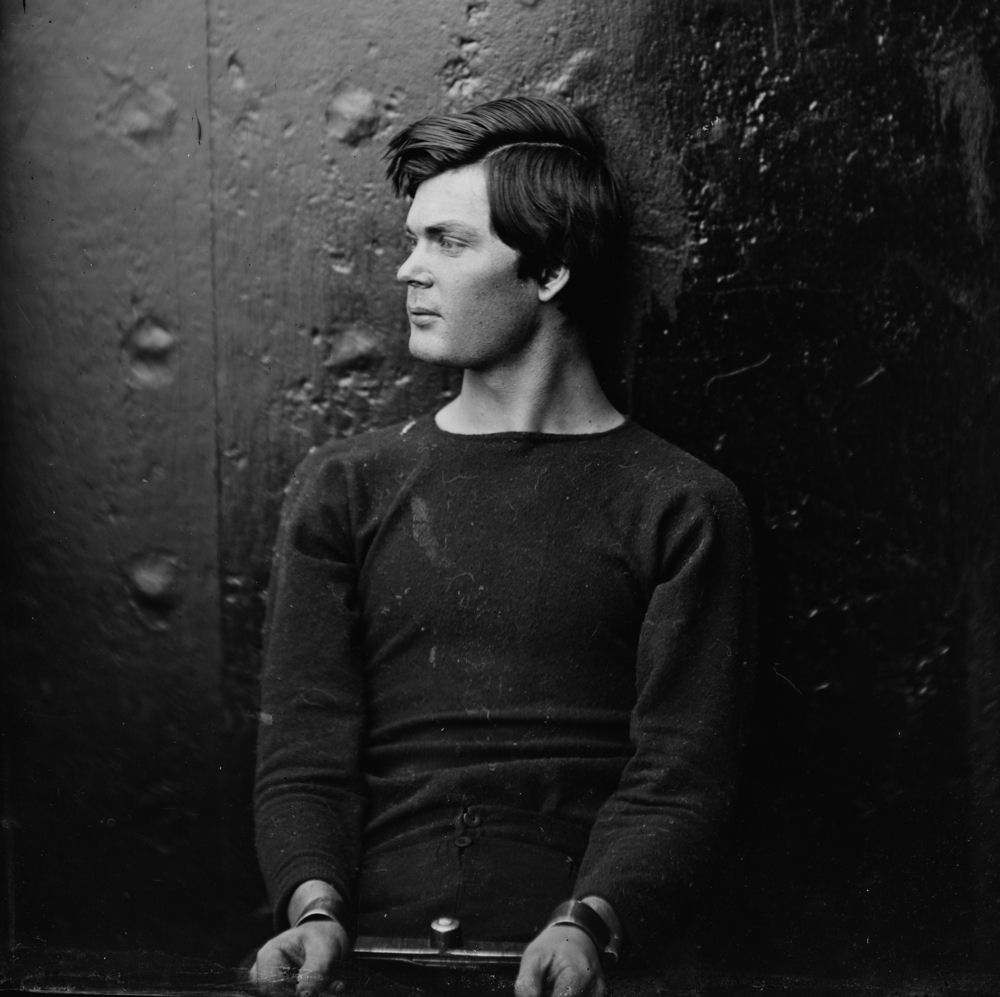

The always photogenic Lewis Powell

In case anyone missed any of that, let’s run through the scenario presented by Neff and Guttridge: William Seward had an armed guard stationed just down the hall from his room. We have no idea why he had an armed guard since the President didn’t even have one, but we’ll just play along and say that he had one. That guard though didn’t respond when Powell came calling at the door, forcing his way in. He didn’t respond when Powell argued with Bell and pushed past him. He didn’t respond when Powell “walked heavy” up two flights of stairs. He didn’t respond when Frederick [Seward] stood on the landing loudly arguing with Powell. He didn’t respond when Powell then physically attacked Frederick, leaving him for dead (or to wander off to his bedroom, or to get up and wander into his father’s room). He didn’t respond when William Bell ran from the house screaming “murder!” He didn’t respond when Powell forced his way into William Seward’s room. He didn’t respond when Powell attacked first Robinson and then Seward. No, it wasn’t until Powell was fighting his way out of the bedroom that Hansell decided to respond. And even then, despite the fact that Powell had nearly killed three people, including the guy that Hansell was assigned to protect, he opted not to use his weapon, choosing instead to become another casualty.

Does all of that make perfect sense to everyone?

If so, then this infinitely fascinating bit of assassination trivia should make perfect sense as well: “The Seward episode was further complicated by a coincidence. Within twenty-four hours of the Good Friday attack, newspapers reported that Emerick Hansell, the State Department messenger on protective duty and knifed on the third floor, had died of his wounds. The obituaries were all but correct. There were two men named Emerick Hansell. One had indeed succumbed in Washington, but he was a farrier at the Union cavalry depot at Giesboro at the edge of the city. His widow was informed that he was kicked in the head while shoeing a horse. He lingered a week, to die just eight hours after the stabbing of his namesake.”

Call me a skeptic if you will, but I am finding it very difficult to believe that that was a ‘coincidence.’ Truth be told, I’m finding it almost impossible to believe that there were two guys named Emerick Hansell living in Washington, DCin 1865, let alone that one of them died within hours of the other being brutally attacked. If such reports did indeed circulate, then they had to be deliberately false reports. And those false reports led to a very predictable outcome:

“The farrier’s death had the effect of stilling questions that only the other Hansell might have answered. Many years would pass before the State Department’s messenger, then in pensioned retirement following a resumed career on the federal payroll, would give his story under strict guarantees of confidentiality. His recollection then was that he had been the third man on the landing, rushing to Private Robinson’s aid, convinced that the man he and the soldier grappled with was Major Augustus Seward, the secretary’s troubled son.”

It is obvious from this passage that Guttridge and Neff based their account of the alleged attack at the Seward residence on Hansell’s belated, off-the-record recollections. The authors appear to be unaware that Hansell’s story is wildly at odds with the accounts of other supposed witnesses, or perhaps they just don’t care.

The Seward family home in Washington, DC

We now have testimony from three guys claiming to have been in William Seward’s bedroom and to have acted in his defense. One of them, Augustus Seward, had no one assisting him and he thought he was fighting against either his father or his father’s nurse. Another of them, Emerick Hansell, was assisted only by Robinson and thought he was grappling with Augustus Seward. The third, George Robinson, thought that he was fighting with a guy he described to a newspaper reporter as having “light sandy hair, whiskers and moustache.” And he, of course, thought that he was assisted by someone who was never identified.

None of the three saw Frederick Seward lying unconscious outside William Seward’s room, but Robinson did see him enter the room. None of them made any mention of the presence of Fanny Seward, though her belatedly released statement would hold that she was in the room as well. None of them saw Frances or Anna Seward either, though you would think they would have come to see what all the commotion was about at some point. Though Powell and Hansell were both supposedly packing heat, and Augustus Seward’s testimony at trial indicated that he retrieved a gun as well, not a single shot was fired that night at the Seward mansion. After being awakened by the commotion, which necessarily would have included Bell’s shouts of murder, Major Seward nevertheless opted to initially respond without a weapon. Hansell apparently responded without his weapon as well. And Bell, ignoring the fact that Seward already had an armed guard and a militarily trained and armed son, felt the need to run down the street seeking outside help.

It’s hard to imagine a more ridiculously contradictory set of stories. Two of the ‘witnesses’ essentially identified each other as the assailant, and the third offered up a description that did not in any way fit the always clean-shaven Lewis Powell. To say that there was reasonable doubt in this case would be a serious understatement, but the tribunal had no problem convicting Powell and sentencing him to death (there were even, as previously stated, contingency plans to have him executed before the trial even concluded).

But then again, Doster did wrap up his ‘defense’ of Powell by delivering a closing argument that began as follows: “May it please the court: There are three things in the case of the prisoner, Powell, which are admitted beyond civil or dispute: (1) That he is the person who attempted to take the life of the Secretary of State. (2) That he is not within the medical definition of insanity. (3) That he believed what he did was right and justifiable. The question of his identity and the question of his sanity are, therefore, settled, and among the things of the past.” With a defense like that, how could he lose?

Lewis Powell’s empty gravesite

Perhaps James Swanson, who appears to fancy himself to be the reigning expert on the Lincoln assassination, can clear up the confusion surrounding what exactly happened at the Seward manor. In his bestselling Manhunt: The Twelve-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer (William Morrow, 2006) Swanson spins a uniquely preposterous account of the alleged attack. Like other self-styled historians, he handpicks facts from the accounts of various alleged participants while conveniently leaving out all the contradictory elements of those accounts.

One thing that Swanson does get right in his overly wordy account is an acknowledgement that Powell’s alleged assignment would have been a very difficult one: “This was a difficult mission even for a man like Powell, a battle-hardened and extremely strong ex-Confederate soldier. Powell had three problems. First, how could he get inside Seward’s house? … Once inside, it was Powell’s job to track down Secretary Seward in the sprawling, three-story mansion … Powell faced a third challenge: he did not know how many occupants … were on the premises.”

In Swanson’s telling of the tale, on the night of April 14, 1865, “Fanny [Seward] watched over her father and listened to the sights and sounds of the never-ending celebrations in the streets.” Of primary interest here is the mention of the “never-ending celebrations.” General Lee had just surrendered to General Grant, the Civil War was all but over, and the nation’s capitol was in a celebratory mood. Just the night before, public buildings and private homes across the city were lit up with candles and gaslights while fireworks exploded overhead, providing, by all accounts, a uniquely awe-inspiring view of the city.

The next day, April 14, was a Friday and those celebrations continued well into the night, with tens of thousands of people taking to the streets to join in the revelry. The Seward mansion sat, as previously noted, right across the street from Lafayette Square, which surely would have been filled that night with a sizable portion of that mass of humanity. Keep that in mind as we work our way through Swanson’s highly dubious account.

“Around 10:00 P.M.,” according to Swanson, Fanny Seward “put down her book, Legends of Charlemagne, turned down the gaslights, and, along with Sergeant George Robinson, a wounded veteran now serving as an army nurse, kept watch over her recovering father.” For the record, Robinson was not yet a sergeant, which is one of many factual inaccuracies that can be found throughout Swanson’s supposedly authoritative books.

Shortly after Fanny had lowered the lights, Lewis Powell approached the front door of the home and “rang the bell … [and] William Bell, a nineteen-year-old black servant, hurried to answer the door.” Amazingly, Swanson knows what William’s age was at the time even though Bell himself was unable to provide that information when asked at trial! In any event, an argument ensued between Powell and Bell and, “For five minutes, the assassin and the servant bickered about whether Powell would leave the medicine with Bell.”

Powell next pushed past Bell and proceeded up the stairs, where, as we know, he encountered Fred Seward and argued with him as well. After appearing to lose the argument, Powell began to retreat down the stairs but then quickly pivoted and attempted to shoot Fred Seward. When the gun failed to fire, “Powell raised the pistol high in the air and brought down a crushing blow to Seward’s head. He hit him so hard that he broke the pistol’s steel ramrod, jamming the cylinder and making it impossible to fire again.”

Broke the steel ramrod?! No shit? I could see possibly bending it, but how do you “break” a steel ramrod? Had Powell or anyone else hit Seward with that kind of force, and then delivered a few more equally devastating blows, he would certainly have killed him. But according to Swanson, Powell didn’t even knock him down (directly contradicting, of course, Bell’s sworn testimony at trial): “Powell moved lightning fast. He shoved Fred aside and struck Robinson in the forehead hard with the knife.” Swanson later informs us that Fred remained conscious and on his feet throughout the ordeal, though he mostly just “wandered around the house like a zombie, babbling the same phrase, ‘It is … it is,’ over and over unable to complete the thought.”

Meanwhile, “The assassin pushed past the reeling sergeant and the waiflike girl blocking his path and sprinted to the bed” where the ailing William Seward lay helpless. According to Swanson, the only thing that saved Seward’s life was Powell’s poor aim, which resulted in him completely missing the motionless secretary of state with his first two knife thrusts. By the time he connected, Robinson had rejoined the fight and was attempting to pull Powell away from Seward. At about that time, “Fanny … screamed, not once, but in a ceaseless, howling, and terrifying wail that woke her brother Augustus, or ‘Gus,’ who was asleep in a room nearby. Fanny then opened a window and screamed to the street below.”

So now, in addition to Bell running down the street screaming “murder,” we have Fanny Seward screaming out an open window. And yet still, with celebrants swarming around the capitol, no one was able to respond in time to even see Powell, let alone try to stop him! Sounds perfectly reasonable to me. As does the fact that “Gus” was able to sleep through the knock on the door, the argument between Bell and Powell, Powell’s noisy ascent of the stairs, Powell’s argument with Frederick, Powell’s attack on Frederick, Powell forcing his way into William Seward’s room, Powell’s attack on Robinson, Powell’s attack on William Seward, and all the screaming that all the victims would undoubtedly have been doing as they were being viciously attacked. Old Gus was a pretty sound sleeper, I guess.

According to Swanson, Augustus Seward and George Robinson then jointly battled Powell, which we already know directly contradicts the sworn testimony of both of them. That fight supposedly spilled over into the hallway outside Seward’s room. At that time, “Secretary Seward’s wife, alarmed by Fanny’s screams, emerged from her third-floor, back bedroom in time to witness the climax of the hallway struggle between Powell and her son Gus. Uncomprehending, she assumed that her husband had become delirious and was running amok. Fred’s wife, Anna, rushed to the scene …”

Apparently Frances and Anna Seward slept even more soundly than Augustus. With their arrival though, Powell was outnumbered six to one, and that didn’t even include Hansell, who, according to Swanson, decided that his best bet was to get the hell out of Dodge: “On [Powell’s] way out, he caught up with Emerick Hansell, who was running down the staircase, trying to stay ahead of the assassin. The State Department messenger, on duty at Seward’s home, was fleeing rather than joining the battle.”

Of course he was. That’s probably why we all remember him being lynched, which is undoubtedly what would have happened if Swanson’s tall tale was true. I guess Hansell slept through most of the ordeal as well, foolishly choosing to flee at the same time as Powell. You’d think he would have just stayed wherever it was that he was hiding. Or run sooner. Those would have been safer options. But then again, since he had a gun and was backed up by at least six people, and the assailant was unarmed, maybe he should have just done his job. That way, he wouldn’t have had to haul his gravely wounded body up two flights of stairs to get into bed before the doctor got there.

It is more than a little odd, I must say, that both Augustus Seward and Frances Seward claimed to initially believe that the ‘intruder’ was actually William Seward “running amok.” Was that a common thing for the secretary of state to do? Even when everyone knew that he was confined to bed and completely immobile?

Mr. Robinson, by the way, had a change of heart after telling a reporter about the intruder with “light sandy hair, whiskers and moustache.” By the time the trial rolled around just a few weeks later, Robinson was sure that Powell was the assailant. That may have been due to the fact that he had received a gold medal, $5,000 in cash, and a promotion. And he later was awarded the knife allegedly used by Powell in the attack.

This is said to be the only known remains of Lewis Powell

It is impossible for me to believe that the alleged events at the Seward home ever took place. All the available evidence overwhelmingly suggests that it was an entirely manufactured affair. Fanny and Frances Seward, as previously discussed, did not live long after the alleged attack. Neither, of course, did Lewis Powell. William and Frederick Seward chose to never speak publicly about the alleged incident. Augustus Seward, George Robinson, William Bell, and (belatedly) Emerick Hansell gave wildly conflicting accounts. And as mainstream historians continue to work diligently to bend the conflicting accounts into some kind of believable storyline, the story just gets more and more ridiculous.

The more deeply immersed in this I become, the more I am convinced that the key to understanding the Lincoln assassination may be in understanding what didn’t happen at the Seward residence. For if the alleged parallel attack on the Sewards never took place, then clearly there was much more to the events of April 14, 1865 than the activities of John Wilkes Booth and a ragtag band of conspirators.

Before wrapping up, let’s take a look at one final curiosity surrounding the alleged attack on the Seward family: in all the accounts that I have read – and I have now worked my way through fourteen books chronicling the Lincoln assassination – it is either stated or implied that Powell (and Bell) ascended just one flight of stairs to get to William Seward’s bedroom, and descended just one flight to exit the house. But Seward’s bedroom was on the third floor of the home, which meant that reaching him (and Frederick and the rest of the cast) would have required first ascending one flight of stairs, then crossing a second-floor landing, and then ascending a second flight of stairs.

That curious fact seems to have remained deliberately obscured for many, many years now. And it’s not hard to figure out why, for if that fact is pointed out, it raises the very obvious question of exactly how Powell would have known to bypass the home’s second floor and proceed directly to the third.

I recommend that you remove all profanity from these articles. Basic common courtesy should inform us that profanity has no place in an article intended for the general public, since it offends many readers. Using profanity in an article lowers the article’s quality and credibility and causes many readers to view the author negatively.

Mmmmkay, buddy, a little reality check for you:

1) The site is not intended for the “general public.” It’s not G-rated even without the cursing.

2) The basic premise of Dad’s work is offensive to a lot of people. I have zero fucks to give.

3) Give me thirty minutes and I’ll find you a shitload of published material with profanity in it.

4) The cursing is the best part, honestly. It’s part of the humor that makes Dad’s bitter reality pills easier to swallow. There’s no way in hell I’d ever censor that.

And here’s the bottom line: Dad left me in charge of safeguarding his legacy, and that means preserving his words, the only really tangible thing we have left of him, exactly as they are. I may someday clean up and publish the features in book form, but that will be in addition to preserving the unaltered content here. And even then I won’t censor, merely trim and polish.

If that’s your takeaway from this amazing research and excellent writing, I’m amazed! I was so enthralled with the revelations – I had to stop and try to remember where the curse words are.

Please don’t cuss? Really? Do you not do ‘adult’ or read in general? You must walk around being offended all day every day.

Mike Griffith is absolutely correct in his assertions. While it may show the personality of the author, it means the material will never reach a higher level. A good editor would polish the personality, trim the vulgar, and let the material presented shine. Not surprised foul-mouthed women and feminized men stood up to thwart any attempt at giving this work real dignity.

Thank you, Alissa, for preserving your fathers work. He has helped show us that history is not just written by the winners, but that the “winners” are not above conspiring in their own self interest and fabricating a self-serving narrative. And it’s silly for someone to be upset about the cursing, but not about the fact that they have been lied to all their lives.

Fcuk off !

Write your own article, pal.

It would open the information to a wider audience.

Thanks for your unsolicited opinion, Sam.

Good for you. Alyssa!

Amazing to me that a person be offended by a couple of “curse words” used to drive home a point and indicate the utter exasperation of the writer when encountering such a cluster-fuck of erroneous and obviously fabricated details, rather than be understandably outraged at the miscarriage of justice that was carried out here!!!

Sadly, maybe the statement made by Jack Nicholson’s character in “A Few Good Men” – “You can’t handle the truth”, is more truth than fiction when referring to so many people nowadays (or even in 1865 it would appear).

I truly commend you on your loyalty and for keeping your Dad’s legacy alive! I, for one, have very much appreciated his refusal to blindly accept some of the propaganda we have been spoon fed for so many years and his contributions to the re-visiting of history!

Well done!

Unsolicited…? You have a comment section. Your father did some very good work. The more people who are exposed to it the better.

Absolutely, and I’m glad that there is still so much robust commentary on his work. However, opinions about whether he should or shouldn’t have included curse words in his work are irrelevant.

Please your father’s words are brilliant and I wouldn’t change a thing! If someone can’t handle the curse words then I suggest they read something else. George Carlin said it best “There are no bad words. Bad thoughts. Bad intentions, and words. I love your father’s writing style. I felt like I lost a friend. A brilliant man!

First of all, I LOVE your father’s work. Thank god it’s still available. This Lincoln piece is AWESOME!! I had always assumed that Seward, due to his infirmity, had been located in a second floor bedroom for easier access by physicians, family members, etc., and for him to get around after his condition improved. It might have been a bigger room, which would more easily accommodate those who were sitting with him. Another factor may be that if he were on the 3rd floor his moaning and groaning may have been upsetting/disturbing to his wife. It reminds me of people setting up a hospital bed in their living room when they are taking care of a seriously ill/dying family member rather than in upstairs in a bedroom.

Mike Griffith…let me guess…lib, dem, snowflake…am I getting warm? In my book, just a tool bag! Mike… you’re being ass raped by their lies and you are more worried that they didn’t say I love you after…get-a-f’ing-clue…that clean enough for ya?!

Dear Mike, basic common courtesy, is my last concern when reading these brilliant articles.

Before you use a word like profanity, just ask yourself who is offended here. Seems to be only you.

You should be offended and outraged by the ridiculous stories told to the general public.

As a non US reader, I sure hope readers outside the US will find a way to this website.

Got the same feeling as mentioned by R. Oatman.

Hell, I’m Irish and, as the world knows, we are acutely sensitive to any form of bad language! I’m serious!

But even I, a notoriously delicate soul as regards to swearing, am not in the least offended by your father’s colourful language.

Your love for your Dad is pleasing to me. Yes, he is owed loyalty and preservation of his work.Extraordinary research. Interesting & super writing style. There is a reason history repeats itself. And as your Father has proven to me it is planned & controlled by those forces in power that continue to lie, steal & kill. I believe there will an an accounting by a righteous Judge. God Bless Young Lady.

I think I spotted a minor typo. Below the (living) image of Powell, about half way down the paragraph.

“He didn’t respond when Frederick Powell stood on the landing loudly arguing with Powell.”

I think Dave meant Frederick “Seward” arguing with Powell.

I love all of your father’s work and have read his articles and all of his books after I discovered his site in 2002. Thank you very much for keeping it available!

Steve

Thanks! I’ve made this correction but noted it in brackets to make it clear that I’ve altered dad’s original words.

Hi, Alyssa,

I always enjoyed David’s way of adding humor to otherwise serious material. His comments such as, “Nothing strange about that,” would leave me laughing out loud. I was first turned on to your father’s work when he was writing about Laurel Canyon. He pointed me towards George Hodel,

which has led to a rewarding interaction with Steve Hodel. I have also read some of David’s books, most notably “Programmed to Kill”. I hated to hear of his illness & passing.

Concerning these comments, Some people can’t bear any level of cussing. I don’t know how they can watch movies or even TV, read books, or much of anything. They get all bowed up over it. My dear wife, whom I love dearly, is like that. We start watching a movie and someone drops an F bomb, she starts with “Oh, here it goes again.” I guess it comes down to how isolated someone is willing to be. This isn’t code era Hollywood people. The 50’s are long ago. Lucy & Ricky Ricardo sleeping in separate beds, how ridiculous, & where did little Ricky come from?

All the Best,

Dan

Well at the risk of getting my own head blown off by all the censorious swearers who have reacted to Mr Griffith I think his point about coarse language in print is has some validity. English has a long tradition of excluding such words from serious publications and it dates back at least to Shakespeare’s day, not the ‘Hollywood code’ which was as I understand it a Catholic-led effort to reign in the proto-pornography of much 1920s film.

I have found Mr Macgowan’s works most illuminating and entertaining and his infrequent vulgarities to be almost always well-timed and appropriate to his very intimate, conversational yet polemical style. However there is a price to pay for such allowances, namely that in my not so very long lifetime we have gone from seldom if ever hearing or using these words to being literally, like Mrs Lackey, unable to eacape them.

Is that Pete Buttigieg “examining” that skull in the final photo? Creepy resemblance.

I’ve been a fan of Dave’s work since the early days and have purchased a few of his books – twice – as once lent out his books remain resolutely gone. : ) I saved all his interviews to share them with all and sundry and listen to them now and again because they’re good for the soul. I thanked Dave for his masterful blend of unique wit and rigorous research many times.

Wish we had his inimitable take on the mass psychosis so often renamed it’s hard to settle on one: CON-vid will do. And that Dark City, “Shut it down!” sci-fi moment become reality with all its attendant tyrannical horrors. How naive we were. The FM/Frankist/Kommie Capstone Event wasn’t 9/11. It was the entree. God help us.

Many thanks and God bless you for keeping your father’s site going, Alyssa!