When we left off on the last outing, two men officially identified as John Wilkes Booth and David Herold had just crossed the Navy Yard Bridge from Washington, DC into Maryland. They were the only two people to cross the bridge after curfew that fateful night, so being allowed to do so was quite the lucky break for the pair. Just as it had been a lucky break for Booth that Lincoln’s bodyguard for the evening, John Parker, had abandoned his post (as had coachman Francis Burns and presidential aide Charles Forbes, all three of whom went next door to drink in the same bar as John Wilkes Booth), and that General Grant and his military entourage had not accompanied the Lincoln party to the theater.

Booth caught numerous ‘lucky breaks’ that night, like having the telegraph service go down right after the assassination. But as Thomas Eckert later explained to a congressional committee, that apparently was a trivial matter: “It did not at the time seem sufficiently important, as the interruption only continued about two hours. I was so full of business of almost every character that I could not give it my personal attention … I could not ascertain with certainty what the facts were without making a personal investigation, and I had not time to do that.”

For those who may have forgotten, Eckert was hired specifically to set up and maintain the telegraph system, which naturally raises the question of what other, more important “business of every character” he had to attend to on a night when keeping the system running should have been, one would think, of utmost importance.

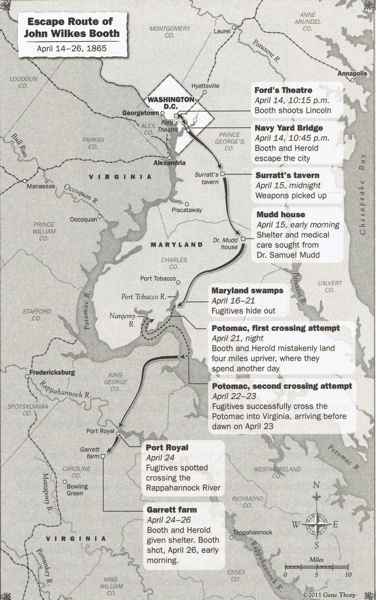

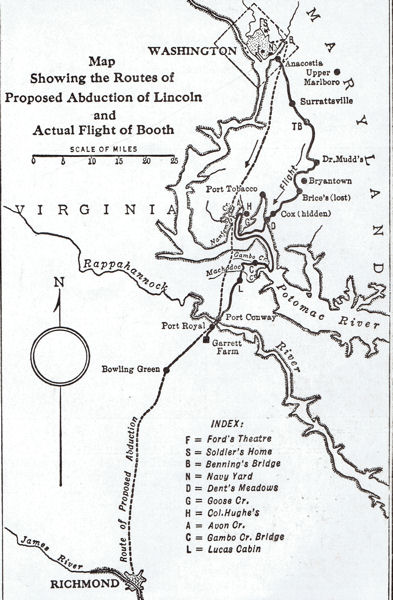

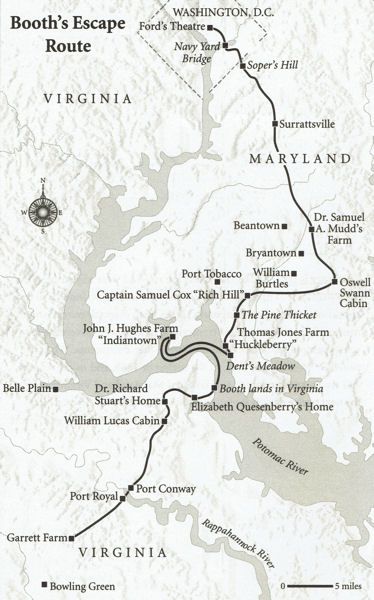

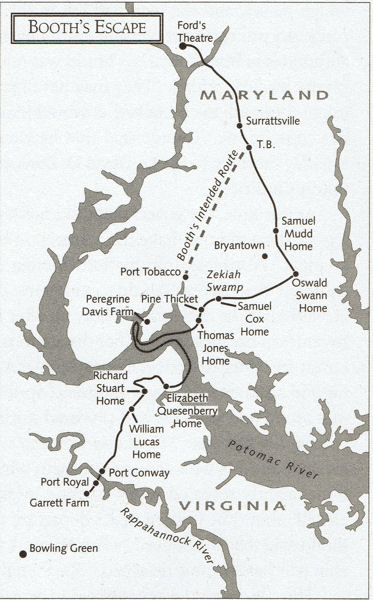

Four versions of Booth’s alleged escape route

Leonard Guttridge and Ray Neff have written in Dark Union that Booth caught another lucky break when, at the same time that the telegraph system mysteriously went down, “someone at the gasworks on Maryland Avenue shut off the gas that fed the lights around the Capitol and westward along Pennsylvania Avenue,” plunging the assassin’s escape route into darkness at a most opportune time. (Leonard Guttridge and Ray Neff Dark Union: The Secret Web of Profiteers, Politicians, and Booth Conspirators That Led to Lincoln’s Death, Wiley, 2003)

Booth also caught a lucky break when his questionable choice of a firearm turned out to be surprisingly adequate for the job. He took a huge risk, it will be recalled, in bringing a Derringer as his only firearm – a risk that was, as James Swanson noted in Manhunt, completely unnecessary: “Booth couldn’t have chosen the Deringer [sic] because he could not obtain a revolver. He had already purchased at least four, and if he did not have any in his hotel room within easy reach, he could have gone out and bought another one. In the war capital of the Union, thousands of guns, including small, lightweight pocket-sized revolvers, were for sale in the shops of Washington.” (James Swanson Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln’s Killer, William Morrow, 2006)

Another lucky break for Booth was that the locks on both of the doors leading into the presidential box at Ford’s Theatre were conveniently broken, rendering them useless. And a spy hole had been drilled into one of them at eye level, so that someone approaching could survey the scene inside the booth before entering. Both of those anomalies were apparently unnoticed by Lincoln and his not-very-security-oriented entourage. And, as previously discussed, a heavy piece of lumber precisely long enough to wedge the door shut happened to be on hand. Many historians have claimed that Booth himself had come by earlier in the day and broken the locks, drilled the hole, and fashioned and hidden the wedge for the door, but no evidence to support such claims has ever been presented.

Booth also caught a lucky break in that he was able to successfully execute an unlikely and extremely risky escape from a crowded theater. As no less a scholar than Bill O’Reilly has had written for him, “A less informed man might worry about being trapped in a building with a limited number of exits, no windows, and a crowd of witnesses—many of them able-bodied men just back from the war.” Donald Winkler was a bit more blunt in his assessment: “It sounded like a foolhardy plan with no chance of success. How could one man with a single-shot derringer, a bullet, and a knife walk nonchalantly through a crowded theater, pass unobstructed through two doors into the State Box, stand behind the president without being seen by the two occupants in the box, kill the president with no one hearing the sound of the shot, leap eleven feet to the stage, take time to yell a message to the audience, and escape through a rear exit? Fulfilling this mission required far more than blind luck.” (Bill O’Reilly and Martin Dugard Killing Lincoln: The Shocking Assassination That Changed America Forever, Henry Holt, 2011; and H. Donald Winkler Lincoln and Booth: More Light on the Conspiracy, Cumberland House, 2003)

Actually, there were obviously more than two occupants in the box and plenty of people heard the shot, but such glaring errors are commonplace in the existing literature on the assassination.

So having caught numerous ‘lucky breaks,’ Booth and Herold rode off separately into the Maryland night, with Booth having a lead on Herold. No mention is ever made of why Powell, who had supposedly attacked the Seward family, and Adzerodt, who was supposed to have killed second-in-command Andrew Johnson, were not included in the escape plan. In any event, Booth and Herold supposedly met up eight miles from the city limits. How they did so in the dark and with no communication devices is anyone’s guess. No mention is made in the literature of Booth asking Herold anything about how the alleged attack at the Seward mansion had gone down, or about the attack on Johnson that had supposedly been planned, or about what had become of Powell and Adzerodt.

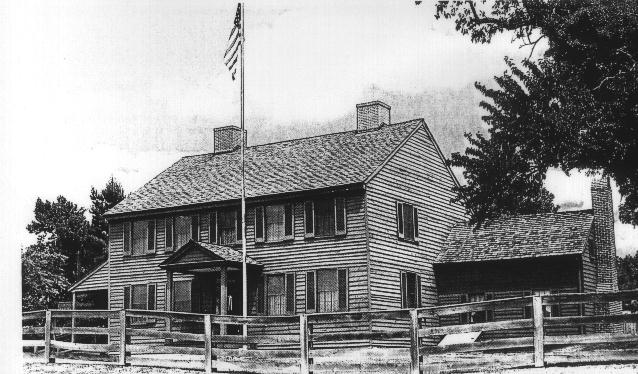

The Surrat Tavern in Surrattsville

The pair’s first stop, so the story goes, was at Mary Surratt’s tavern in Surrattsville, run by John Lloyd. They allegedly arrived there around midnight. Lloyd, known as a raging drunkard, allegedly supplied the pair with two carbines, field glasses, and booze. By many accounts, his confession to such high crimes was obtained through torture. And it is never explained why the pair wouldn’t have already had those items, and various other provisions, from the outset. Lloyd became a witness for the prosecution at the pseudo-trial of the conspirators. Of course, his other option was certain conviction and probable execution, so he was highly motivated to tell the story the government wanted him to tell.

The pair’s next stop – at about 4:30 in the morning on April 15, 1865, with Lincoln still clinging to life – was at the home of Dr. Samuel Mudd, who gained the dubious distinction of being the only person along Booth’s alleged escape route to be prosecuted and convicted. “Wanted” posters issued by Secretary of War Edwin Stanton warned that “All persons harboring or secreting the conspirators or aiding their concealment or escape, will be treated as accomplices in the murder of the President and shall be subject to trial before a military commission, and the punishment of death.” As we shall see though, various historians have identified at least two dozen people who supposedly provided aid and comfort to the fugitives, and none of them, other than Mudd, were ever prosecuted for their alleged crimes and all of their names are now long forgotten.

The home of Dr. Mudd and family

Booth and Herold supposedly introduced themselves to Mudd using the aliases of Tyson and Henson, and by some accounts, Booth wore a fake beard – which of course makes perfect sense since Booth had chosen not to don a disguise before committing the crime, and had left his real name scattered about the crime scene and the escape route. And by virtually all accounts, Mudd knew Booth and had had prior dealings with him, so the good doctor would surely have seen through a cheap disguise. For the record, Mudd claimed that he did not recognize the man he treated as John Wilkes Booth, and he could not identify David Herold from a photograph.

Herold, meanwhile, maintained that he had crossed the bridge out of Washington on the afternoon of April 14 and was long gone from the city when Lincoln was shot. He also claimed that he had not gone to the Mudd house with Booth or anyone else. And evidence does indeed suggest that Herold spent the afternoon of April 14 on a horseback ride in the Maryland countryside. And he did so with – and I couldn’t possibly make this stuff up – a sixteen-year-old kid by the name of Johnny Booth, who was apparently not related to the far more famous John Booth. Herold and the young Booth got drunk and passed out and were found the next morning by Johnny’s father. Johnny and his father, of course, were not called upon the testify at the mock trial.

Meanwhile, Mudd repaired the damage to his visitor’s leg, which he later described in a statement as a not very serious or painful wound, and fashioned a splint for him. He then offered the exhausted travelers sleeping accommodations. After catching some sleep and paying the good doctor for his services, the pair left later that day. At the infamous trial of the conspirators, the story did not pick up again until nine days later, on April 24, when the pair allegedly took a ferry across the Rappahannock River. Various historical narratives have filled in those missing nine days, though not necessarily with a story that has much credibility.

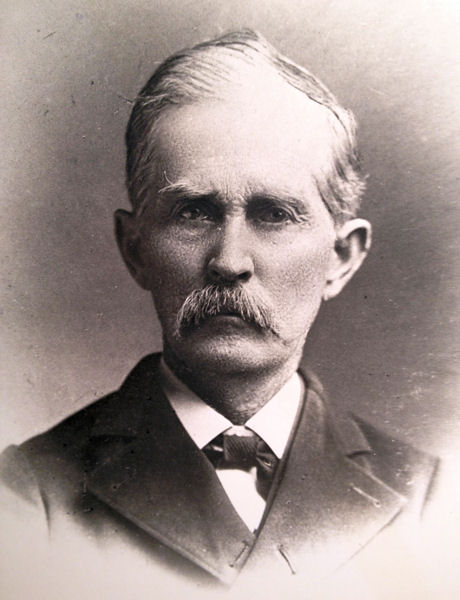

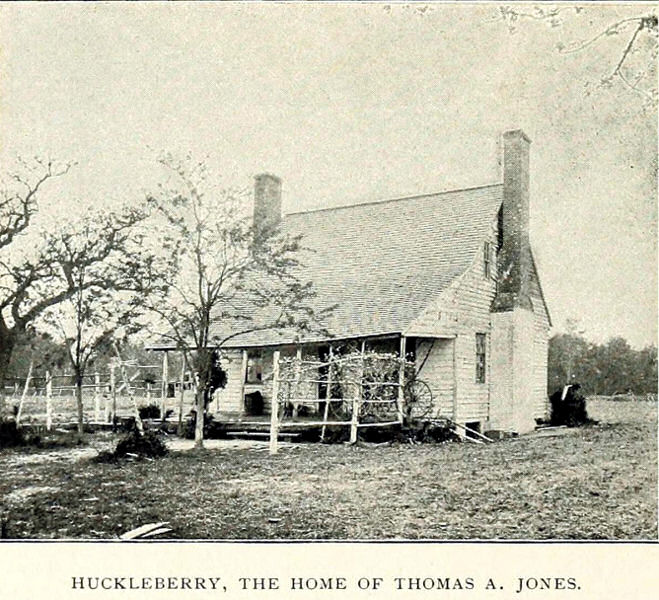

Thomas Jones and namesake

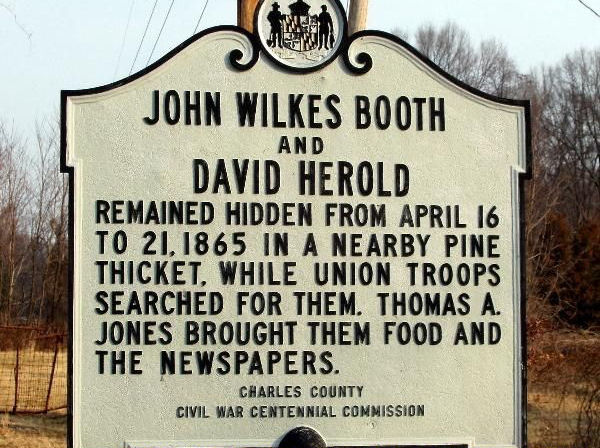

According to Lincoln folklore, a guy by the name of Oswell Swann (sometimes identified as Oswald Swann), described as being half black and half Indian, guided the pair to the home of a Samuel Cox at about 1:00 AM on April 16, 1865. Cox allegedly advised Booth and Herold to hide out in a nearby pine thicket, and had his overseer, Franklin Robey, guide them there. He then summoned Thomas Jones to supply them with food, blankets, and newspapers. Needless to say, none of these men were ever prosecuted for their alleged capital offenses.

Samuel Cox

Booth and Herold supposedly spent five long days cooling their heels in that pine thicket. During that time, they had to keep quiet at all times for fear of alerting any nearby patrols to their whereabouts. They couldn’t light a fire to keep warm. And Booth is generally described as being immobilized and in considerable pain from his injury (the one that Dr. Mudd described as not particularly painful). According to the best-selling Manhunt, for example, “Booth never rose from the ground during the time in the thicket.” So the wealthy, accomplished, well-bred actor spent five agonizing days lying hungry and motionless on the cold, unforgiving ground of a Maryland pine thicket. Sounds perfectly reasonable.

One problem with that tall tale though concerns the fate of Booth’s and Herold’s horses. It is agreed that they surely had horses when they arrived at the pine thicket, and they would have had to get rid of them to avoid giving away their position to any passing patrols. So what happened to them? In Manhunt, James Swanson tells the following tale: “Davey [Herold] untied both horses and led them by the reins to a quicksand morass about a mile from the pine thicket. Quickly, he shot each one in the head with a pistol or the carbine, and then sank their bodies, still accoutered with saddles, bits, bridles, stirrups, and all. There they rest in an unmarked grave, their skeletons undiscovered to this day.”

Here Swanson has acknowledged something that historians agree on: despite one of the world’s most exhaustive manhunts, no trace of the two horses was ever found. According to the guy who actually writes the books that Bill O’Reilly puts his name on, “A combined force of seven hundred Illinois cavalry, six hundred members of the Twenty-second Colored Troops, and one hundred men from the Sixteenth New York Cavalry Regiment now enter the wilderness of Maryland’s vast swamps [on April 18, 1865] … Incredibly, eighty-seven of these brave men will drown in their painstaking weeklong search for the killers.” No large animal carcasses were found on that search, or on any other searches. O’Reilly doesn’t mention, by the way, how many of those eighty-seven alleged drowning deaths involved members of the Twenty-Second Colored Troops (sorry – I couldn’t resist).

Historians also agree that Booth was far too seriously injured to be of any help to Herold, leaving Herold solely responsible for disposing of the horses. There are, generally speaking, two versions of the ‘story of the disappearing horses,’ both of which are laughably absurd. One commonly told fable holds that Herold led the two horses into quicksand; the other posits that he shot and buried them. Swanson has essentially weaved a new version of the tall tale by combining the two.

Some historians just avoid any mention of the disappearing horses trick, probably out of a desire to not sound like buffoons. But others have no problem with repeating tales that have stood unchallenged for well over a century despite being easily discredited. Because the reality, dear readers, is that there is no rational explanation for how two horses and all the gear accompanying them could have just vanished into thin air. Only in some fantasy world would it be possible for one man, working alone in fairly primitive conditions and with no tools at his disposal, to dig graves deep enough to completely conceal two very large animal carcasses without even leaving mounds for searchers to find. And even if he could somehow dig the holes, how would one man get those very heavy carcasses into those miraculously excavated graves? And wouldn’t shooting them be a very risky maneuver, since gunshots tend to attract attention? It seems rather unlikely then that Herold shot the horses and then buried them both with his bare hands.

Equally preposterous is the claim that Herold led the horses into quicksand and let them sink to their deaths. Horses can be rather obedient creatures, to be sure, but they certainly aren’t stupid and they won’t willingly walk into what they would surely perceive as a deathtrap. And how exactly would someone go about leading them into quicksand? Wouldn’t that require that the person doing the leading would have to walk out into the quicksand ahead of the horses? Those are rather moot points though given that Wikipedia describes quicksand as “harmless,” and notes that “People falling into (and, unrealistically, being submerged in) quicksand or a similar substance is a trope of adventure fiction, notably in movies.”

It doesn’t actually happen, you see, in real life. But that hasn’t stopped mainstream historians and academics from promoting such nonsense for decades.

As previously noted, Swanson has combined the two versions of the ‘disappearing horses’ fable. No graves needed to be dug because the bodies were disposed of in quicksand, though horse-swallowing quicksand pits only exist in movies and TV shows from the 1960s – and in bestsellers that begin with the words, “This story is true.” And in this particular version of the fable, Herold didn’t have to lead the horses into the mythical quicksand, he just led them to it. But what Swanson leaves out is an explanation of how Herold single-handedly drug or pushed those half-ton horse carcasses into a fictional quicksand pit. The only way that could actually happen is in a cartoon.

In any event, after allegedly spending five long days lounging in a Maryland pine thicket, our antiheroes supposedly emerged to attempt a crossing of the Potomac River in a boat supplied by local fisherman Henry Rowland. Their first attempt though failed when the ‘pair that couldn’t row straight’ supposedly paddled the wrong direction and ended up in Nanjemoy Creek, still on the Maryland side of the Potomac. Not to worry though – they went to a farm owned by Peregrine Davis and operated by his son-in-law, John Hughes, who happily put his life on the line by feeding and sheltering the fugitives.

The next night, April 21, Booth and Herold chose not to attempt a second crossing of the Potomac, for reasons never explained by historians. It had been a full week since the assassination and the most wanted men in America had failed to put much distance at all between themselves and Washington, but they apparently weren’t in any hurry.

Elizabeth Quesenberry and her home

The dynamic duo allegedly made a second attempt the next night and successfully navigated into Machodoc Creek, near the home of Elizabeth Quesenberry. They arrived at Quesenberry’s home at around 1:00 PM on April 23. The lady of the house promptly sent for Thomas Harbin, who was reportedly Thomas Jones’ brother-in-law. Harbin arrived at about 3:00 PM with horses and two associates, William Bryant and Joseph Baden. The five men then rode to the home of Dr. Richard Stuart, who was apparently related in some way to General Robert E. Lee.

Thomas Harbin

Dr. Richard Stuart

Stuart directed the party, which arrived at around 8:00 PM, to the cabin of a freed slave by the name of William Lucas – because, you know, freed slaves were highly motivated to assist Lincoln’s alleged assassin. From there, Booth and Herold were supposedly transported by son Charley Lucas to Port Conway hidden under a load of straw in a wagon. In Port Conway, the fugitive pair hooked up with three Confederate soldiers by the names of Mortimer Ruggles, Absalom Bainbridge and William Jett, who by some accounts had been under the command of notorious Confederate intelligence operative John S. Mosby (Mosby, by the way, would soon enthusiastically campaign for and serve in the cabinet of Ulysses S. Grant, the man who had defeated his supposedly beloved Confederacy).

Booth, Herold, Ruggles, Jett and Bainbridge, along with a few horses, purportedly took a ferry across the Rappahannock River. At approximately 3:00 PM on April 24, 1865, they arrived at the Garrett home. The gravely injured, or not so gravely injured, John Wilkes Booth stayed at the home while Herold rode on to Bowling Green with his new friends. Booth spent the night with one of the Garrett sons while Herold and Bainbridge slept at the home of Joseph and Elizabeth Clarke. Herold returned the next day with Ruggles and Bainbridge, though Jett stayed behind in Bowling Green, from where he would soon lead a posse to the Garrett farm.

Ruggles

Bainbridge (both circa 1890)

Jett

Booth and Herold spent the next night, April 25, supposedly locked in the Garretts’ tobacco barn, making them easy prey for the posse that would soon arrive. The Reverend Richard Garrett, however, who was just eleven at the time of the assassination, would later note that the barn actually had double doors on all four sides and large windows in the upper story. William H. Garrett would add that some of those doors and windows fastened on the inside. There was, therefore, no way to actually lock the fugitives inside, another unfortunate fact that has been swept aside by historians.

The posse that would allegedly end the life of John Wilkes Booth arrived at the Garrett home at around 2:00 AM on April 26, 1865. A few hours later, Booth, or someone playing the part of Booth, had been shot. In due time, Dr. Richard Stuart, William Bryant, Elizabeth Quesenberry, Samuel Cox, Thomas Jones, the Garrett sons, and various others were arrested and taken to the Old Capital Prison. Curiously though, they were all freed without being charged. All but Dr. Mudd.

Sign commemorating fictional historical events

Meanwhile, as Booth and Herold were following their convoluted path to the Garrett farm, a massive manhunt spearheaded by Edwin Stanton was underway. We shall pick up there on the next outing.

Stanton is my mystery man.

Powell (the Seward “assassin” has noted on his tombstone that he was in a Florida regiment and was a member of Mosby’s Rangers. Another link to Mosby as in this chapter.