Before resuming where we left off, I need to tack on some info here that should have been included in earlier installments. First off, there were, as it turns out, at least three additional suspicious deaths that followed closely on the heels of the Lincoln assassination, so let’s take a quick look at those. And as I’m sure it will be recalled, these deaths are in addition to all the other curious deaths and confinements that have previously been discussed.

First up for review is Colonel Levi C. Turner, who was appointed Assistant Judge Advocate for the Army on August 5, 1862, which positioned him to be second-in-command to Judge Advocate Holt during the farcical ‘trial of the conspirators.’ The colonel also worked closely with notorious NDP chief Lafayette Baker during and after the Civil War to investigate suspected subversive activities. Turner died of unstated causes on March 13, 1867, less than two years after Lincoln was slain and about sixteen months before Baker himself turned up dead.

Also up for review is our old friend Silas Cobb, the guy who was in charge of guarding the Navy Yard Bridge and enforcing the curfew on the night of the assassination. Cobb was the accommodating gent who allegedly allowed both Booth and Herold to escape from Washington and then failed to offer any reasonable explanation for his actions, and of course suffered no repercussions for those actions. Cobb turned up dead in November 1867, two-and-a-half years after Lincoln was shot. According to reports, he was the victim of a drowning accident.

Finally we have Henri Beaumont de Sainte-Marie, the chap who was credited with tipping off authorities to the whereabouts of John Surratt, ultimately leading to Surratt’s arrest, extradition, and failed prosecution. De Sainte-Marie died at the relatively young age of forty-one while still awaiting a claims court decision on the hefty reward promised for information leading to Surratt’s capture.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

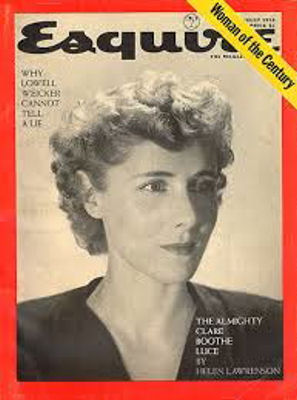

I also discussed in a previous post the fact that former British First Lady Cherie Blair is a descendant of the Booth clan, thereby demonstrating that the Booth family has continued to wield political power into the modern era. What I didn’t know at the time was that another member of the Booth dynasty wielded considerable power on this side of the Atlantic right up until her death at the infamous Watergate Apartments on October 9, 1987.

She was hiding right in plain sight, disguised only by the “e” that her branch of the family had added to the Booth name to mask the association. That wielder of power was none other than Clare Boothe Luce, who, along with her husband Henry Luce – a Skull and Bonesman who became a publishing magnate, launching such influential magazines as Time, Life, Fortune, and Sports Illustrated – was a longtime asset of the Central Intelligence Agency.

Boothe was born on March 10, 1903 to unmarried parents who lived a shadowy life and moved around a lot. Her mother was known to use at least three aliases and her father used at least two. Clare briefly flirted with being an actress before embarking on a career as a journalist, war correspondent, politician and diplomat. Curiously, another woman born in 1903 and also known as Claire Luce also became an actress, creating a good deal of confusion after Clare Boothe became Clare Luce.

Clare Boothe Luce

Clare Boothe Luce had the distinction of being the first American woman named to a key diplomatic post, serving as the US Ambassador to Italy from 1953 to 1956. In 1959, she very briefly served as the US Ambassador to Brazil before resigning. From 1943 to 1947, she had served in the House of Representatives, representing Connecticut. During that time, she served on the House Military Affairs Committee, because she naturally knew a lot about military affairs.

During the 1960s, her and her husband busied themselves with sponsoring anti-Castro groups seeking to return Cuba to its former status as a US puppet-state. In 1973, she was appointed to the President’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, because she obviously also knew a lot about foreign intelligence. In 1983, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Boothe Luce was also a Dame of Malta.

It is a strange world indeed when well over a century after the first acknowledged assassination of a sitting US president (historians don’t generally have much to say about the untimely deaths of William Harrison, who served for just one month, or Zachary Taylor, who served for some sixteen months), members of the alleged assassin’s family were still wielding considerable political power on both sides of the Atlantic. Last time I checked, there weren’t any members of the Guiteau, Czolgosz, Oswald or Sirhan families occupying such positions of power.

And now, we return to our regularly scheduled programming ….

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

While Booth and Herold were supposedly taking their time getting from Washington to Garrett’s farm (traveling a distance of less than 100 miles in a week-and-a-half), the largest manhunt in the young nation’s history was underway, coordinated by our old friend, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. From the outset, Stanton’s goal seemed to be to avoid actually apprehending John Wilkes Booth and some of the other alleged conspirators.

Stanton had considerable manpower at his disposal, including idle US military forces in Washington, the Metropolitan Police, Lafayette Baker’s detective force, US Cavalry forces, and provost marshals. Working closely with Stanton were Metro Police Superintendent A.C. Richards, Washington Provost Marshall Major James O’Beirne, and General Christopher Columbus Augur, commander of US military forces in Washington. To say that Stanton misappropriated the available manpower would be a rather charitable assessment.

A.C. Richards

According to Bill O’Reilly’s error-filled bestseller, Killing Lincoln, there were three routes leading out of Washington into Virginia – the Georgetown Aqueduct, Long Bridge, and Benning’s Bridge – and just one, the Navy Yard Bridge, leading into Maryland. The Confederacy-friendly path into Maryland was by far the most likely route for an assassin to take, so it naturally was completely ignored.

The first troops to find themselves accidentally on the correct route were led by a David Dana. Dana just happened to be the brother of Assistant Secretary of War Charles Dana, who served directly under Stanton and who decided that the patrol’s presence on the trail of the alleged assassins was pointless and instead sent his brother’s troops on a wild goose chase. Major O’Beirne also found himself accidentally on the right trail, so he of course was recalled to Washington.

As previously mentioned, Stanton’s first dispatch after the shooting of Lincoln was not written until 1:30 AM and was not sent until 2:15 AM, about four hours after the shot was fired. That dispatch made no mention of John Wilkes Booth, despite the fact that numerous witnesses supposedly (but not actually) immediately identified Booth as the assailant. Booth’s name didn’t appear in a telegram until 4:15 AM, conveniently too late to make the morning papers. A telegram sent to the police chiefs of northern cities contained no mention of the name Booth.

Initial press reports, based on information leaked by Stanton himself, identified John Surratt as the perpetrator of the fictional attack on the Seward family. When it later became known that Surratt was nowhere near Washington at the time of the attack, Lewis Powell/Paine, who bore no physical resemblance whatsoever to John Surratt, was substituted in as the perpetrator of the alleged assassination attempt.

Christopher Columbus Augur

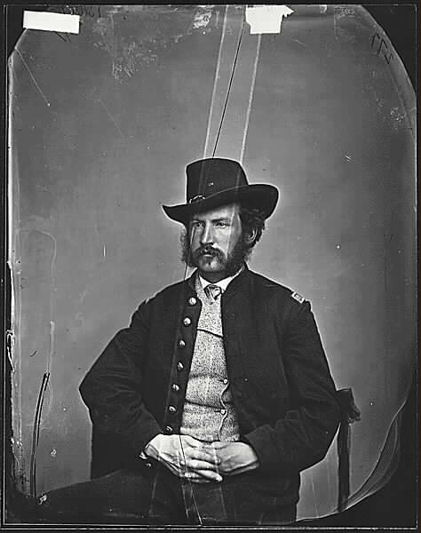

James O’Beirne

The first telegram dispatched by the War Department was a curiously worded message to General Grant, which read: “The President was assassinated tonight at Ford’s Theatre at 10:30 tonight & cannot live. The wound is a pistol shot through the head. Secretary Seward & his son Frederick, were also assassinated at their residence & are in a dangerous condition.” One would think that it would go without saying that someone who had been “assassinated” would be in “a dangerous condition.” Luckily though, neither of the Sewards were actually assassinated, although news of their ‘deaths’ quickly circulated around Washington.

One of the earliest actions taken by investigators was raiding the room at the Kirkwood Hotel allegedly rented by George Atzerodt for the purpose of assassinating Andrew Johnson. According to Guttridge and Neff, writing in Dark Union, “The room was registered as Atzerodt’s but had not been slept in. The Kirkwood’s day clerk, who had entered Room 126 earlier that morning, found nothing and said so. His testimony was ignored.” When detectives entered that very same empty and unused room, they allegedly uncovered a wealth of evidence.

Supposedly recovered from the room were a bankbook issued to John Wilkes Booth, a loaded revolver, three boxes of pistol cartridges, a map of the southern states, a Bowie knife, and a handkerchief with Booth’s mother’s name embroidered on it. Booth’s room at the National Hotel, Room 228, was similarly raided with additional evidence supposedly recovered, including a business card containing John Surratt’s name and a letter from Samuel Arnold conveniently implicating both he and McLaughlin, despite the fact that Arnold and McLaughlin, like Surratt, were nowhere near Washington at the time of the assassination.

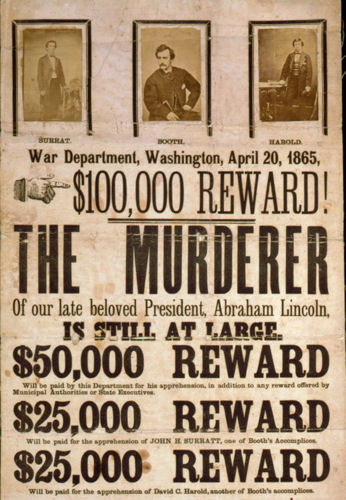

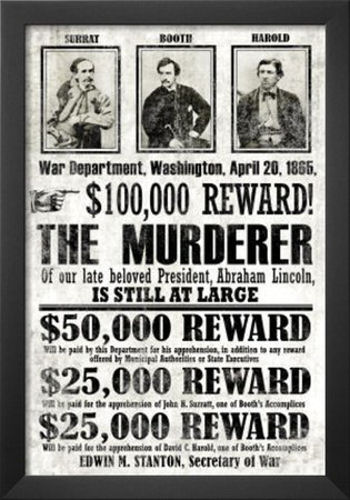

“Wanted” posters issued by the War Department were wildly, and probably deliberately, inaccurate. John Surratt’s and David Herold’s names were both spelled incorrectly, the photo of Herold was of him as a schoolboy, which clearly wasn’t an accurate representation of how he looked circa 1865, and the photo of Surratt wasn’t John Surratt at all. In a blatant act of historical revisionism, corrected posters were issued much later. One widely circulated poster that was issued after Lewis Paine was already in custody inexplicably offered a reward for Paine and contained a richly detailed 160-word description of the already incarcerated suspect, along with a mere 42-word description of the guy who was still at large, John Wilkes Booth.

Original “Wanted” poster

Revised “Wanted” posters

The first alleged conspirator to be arrested was the hapless Ned Spangler, who was taken into custody at Ford’s Theatre on the night of the assassination. Samuel Arnold and Michael McLaughlin, implicated through what appears to have been planted evidence, were arrested on April 17, 1865, the former at Fort Monroe and the latter in Baltimore. Later that night, Mary Surratt and Lewis Powell were both arrested at Surratt’s boardinghouse. George Adzerodt was taken into custody in the early morning hours of April 20 in Maryland, following – by one account – a tip from his police detective brother. Dr. Mudd was arrested on April 24, four days after Captain William Wood, a close associate of Stanton and the warden of the Old Capitol Prison, had begun watching his home.

Why authorities drug their feet for several days before arresting Mudd even while rounding up some 2,000 other suspects who ultimately were not charged is another of the many unanswered questions surrounding the Lincoln assassination and its aftermath. In any event, that left just two of the alleged conspirators at large, David Herold and John Wilkes Booth. Finding them was going to require a specially assembled team – a team that would uncannily know just where to go.

The elite posse was assembled by NDP chief Lafayette Baker on April 24. The group thereafter all but made a beeline to the area around Garrett’s farm. How they knew to go there is a question not often addressed by historians. For the record, Baker claimed that he was tipped off by “an old Negro,” but said person was never identified and he or she never stepped forward to collect the substantial reward offered. A House Committee noted that, “upon what information Colonel Baker proceeded in sending out the expedition … is in no manner disclosed or intimated in his official report.”

An 1867 Minority Report of the Judiciary Committee of the House of Representatives offered what were, by today’s standards, shockingly frank assessments of Baker’s character, such as, “Although examined on oath, time and again, and on various occasions, it is doubtful whether he [Baker] has in any one thing told the truth even by accident,” and “there can be no doubt that of his many previous outrages, entitling him to unenviable immortality, he has added that of willful and deliberate perjury; and we are glad to know that no one member of the committee deems any statement made by him as worthy of the slightest credit. What a blush of shame will tinge the cheek of the American student in future ages, when he reads that this miserable wretch for years held, as it were, in the hollow of his hand, the liberties of the American people.”

The posse assembled by Baker was led by his cousin, Lt. Luther Baker, and Lt. Col. Everton Conger, who had served as an aide to Lafayette Baker. Both had returned to civilian life and were recruited specifically to lead the mission. They were joined by Lt. Edward Doherty and a detachment of twenty-five soldiers. After completing the mission, all involved signed quitclaims and collected a substantial amount of reward money. One of the troopers, as fate would have it, had met Booth previously; some 33 years later, on April 20, 1898, he issued the following published statement: “It was not Booth nor did it resemble him …” Many Americans had reached that conclusion years earlier.

Edward Doherty

Everton Conger

At the Garrett home, the guy later identified as John Wilkes Booth introduced himself as John W. Boyd. Herold was introduced as his cousin, David Boyd. During the standoff in the barn with the pair’s would-be captors, the name “Booth” was never spoken. When Herold surrendered and exited the barn, leaving his companion behind, he insisted that he did not know the other man, who he claimed was named Boyd. Boyd/Booth was wearing a Rebel uniform and did not have on a ring that Booth reportedly always wore.

It was not until he had been shot and lay dying that the suspected assassin was addressed by Luther Baker as “Booth.” According to Baker’s account, the mortally wounded man “seemed surprised, opened his eyes wide, and looked about,” as if he too was looking for the elusive John Wilkes Booth. At 7:15 AM on the morning of April 26, 1865, Booth/Boyd drew his last breath, some two-and-a-half hours after being shot, allegedly by Boston Corbett.

Mainstream authors and historians have labored long and hard to convince readers that Booth’s body was positively identified, leaving no doubt in the public mind that justice had been served. James Swanson, for example, has written in Manhunt that, “On the Montauk, several men who knew Booth in life, including his doctor and dentist, were summoned aboard the ironclad to witness him in death. It was all very official. The War Department even issued an elaborate receipt to the notary who witnessed the testimony. During a careful autopsy …” The same James Swanson has also written, in Lincoln’s Assassins, that, “When the assassin’s body was brought back to Washington, the government took rigorous steps to confirm the identity of the man killed at Garrett’s farm … Witnesses who knew Booth in life were summoned to identify him in death.” William Hanchett, in The Lincoln Murder Conspiracies (his contemptible attempt to ‘debunk’ so-called ‘conspiracy theories’), has claimed that “Booth’s body was identified beyond any possibility of a mix-up at a coroner’s inquest on April 27, 1865.”

All such proclamations are rather brazen and unconscionable acts of historical revisionism. The reality is that the body was not autopsied and it was processed in-and-out of Washington in record time. A mere forty hours passed between the death of the man at Garrett’s farm and the secret, late night disposal of his body, and that included the time needed to transport the corpse back to Washington. To this day, that initial burial site remains a mystery and several different versions of the disposal of the body have been published.

For reasons never explained in the historical record, the body was not transported back to Washington by the military detachment, but was instead escorted by only three men: Luther Baker, prisoner Willie Jett, and one unnamed soldier. Before reaching Washington, Jett somehow managed to, uhmm, ‘escape.’ The body was carried by steamer up the Potomac River, then transported by tugboat to the Washington Navy Yard and placed aboard the ironclad Montauk in the dead of night, at 1:45 AM on April 27, 1865, bypassing normal procedures. Before the day was done, the body would be covertly disposed of. The captain of the Montauk would later say that he “was not present at either time (arrival or disposal) or I should have put a stop to it.” The commandant of the Navy Yard would add that, “The removal of the body was entirely without my knowledge, an unusual transaction.”

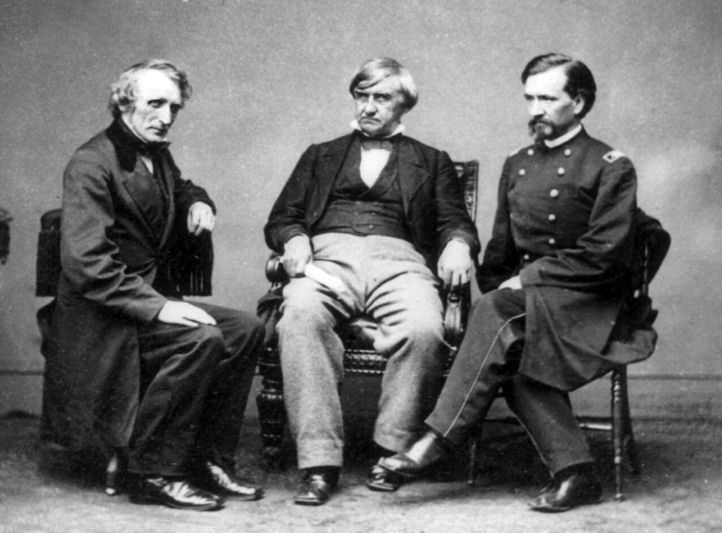

Prosecutor John Bingham (left) and Judge Advocate Joseph Holt (center)

Dispatched to the Montauk to oversee the identification of the body were such disreputable characters as Surgeon General Barnes, Judge Advocate Joseph Holt, prosecutor/persecutor John Bingham, Stanton underlings Thomas Eckert and Lafayette Baker, and two of Baker’s most trusted men, Luther Baker and Everton Conger. Edwin Stanton had ordered Lafayette Baker and Thomas Eckert to personally intercept the boat carrying the body and clandestinely get it aboard the Montauk.

During the alleged inquest, none of Booth’s peers in the theater community, many of whom were present in Washington at the time, were brought onboard to ID the body. No members of the Booth family were enlisted to view the body. None of Booth’s alleged co-conspirators, many of whom were being held on the very same ship, were allowed to ID the body. According to Dark Union, “thirteen people were permitted to view the body. All but the war photographer Alexander Gardner, his assistant, and a hotel clerk were connected with the War Department.” If we’re being honest here, that should read, “all but possibly the hotel clerk were connected with the War Department.”

Even within the government’s handpicked and limited cast of witnesses, there was disagreement as to whether the body was that of Booth. Dr. John Frederick May, who had previously seen Booth as a patient, noted that “there is no resemblance in that corpse to Booth, nor can I believe it to be him.” May added that the corpse “looks to me much older, and in appearance much more freckled than he was. I do not recollect that he was at all freckled.” Dr. May would later write that the corpse’s “right limb was greatly contused, and perfectly black from a fracture of one of the long bones.” Surgeon General Barnes’ report to Stanton, however, held that it was “the left leg and foot” that were injured and “encased in an appliance of splints and bandages,” thus clouding the waters even on such straightforward issues as which of the corpse’s legs was injured.

Dr. John Frederick May

After the hasty identification charade, and without anyone who was actually close to Booth in life having seen the body, and without any public display of the body, and without any photographs of the body that would ever see the light of day, the corpse was quickly disposed of by either Lafayette Baker and Thomas Eckert, or Lafayette and Luther Baker, depending upon who is telling the tale. Following the announcement that the body had been disappeared, shouts of “hoax!” rocked Washington, with many convinced that Booth hadn’t been captured or killed and was still free.

On July 28, 1866, Senator Garrett Davis of Kentucky voiced his doubts about the identification of Booth: “I have never seen any satisfactory evidence that Booth was killed.” Senator Reverdy Johnson of Maryland, who had played a role in the mock trial, came back with: “I submit to my friend from Kentucky that there are some things that we must take judicial notice of, just as well as that Julius Caesar is dead.”

Davis though remained decidedly unconvinced: “I would rather have better testimony of the fact. I want it proved that Booth was in that barn. I cannot conceive, if he was in the barn, why he was not taken alive. I have never seen anybody, or the evidence of anybody, that identified Booth after he is said to have been killed. Why so much secrecy about it? … There is a mystery and a most inexplicable mystery to my mind about the whole affair … [Booth] could have been captured just as well alive as dead. It would have been much more satisfactory to have brought him up here alive and to have inquired of him to reveal the whole transaction … [or] bring his body up here … let all who had seen him playing, all who associated with him on the stage or in the green room or at the taverns and other public places, have had access to his body to have identified it.”

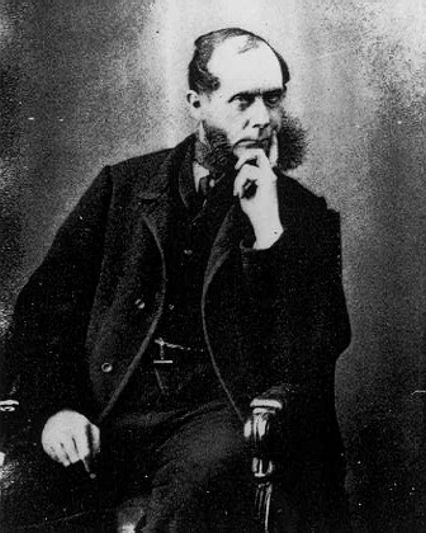

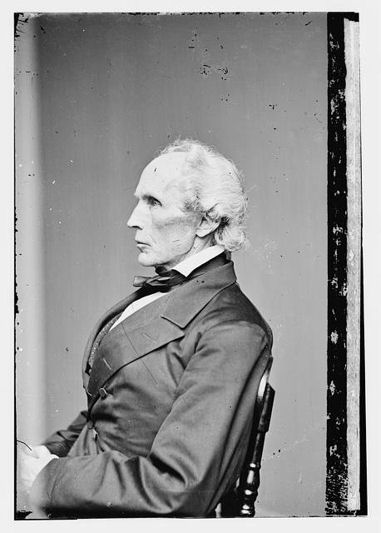

Senator Reverdy Johnson

Senator Garrett Davis

There was no way the powers-that-be were going to allow that to happen, of course, since the body clearly wasn’t that of John Wilkes Booth. Had it been, the government surely would have taken the actions necessary to convince a skeptical public. But such actions weren’t really necessary in 1865, just as they aren’t today. The omnipotent ones can tell us, for example, that Osama bin Laden was killed and his body promptly disposed of – and the majority of us will accept it as the gospel truth.

And those malcontents who choose not to accept a proclamation that lacks any objective proof? Well, they don’t really matter. Just as the voices of reason didn’t really matter 150 years ago.

Mary Todd Lincoln shot Abraham Lincoln with that woman’s gun, in her left hand while she pretended to caress her husband’s head in the dark.

Proof: Her personal assignment of the dirty cop to protect him who got drunk across the street with no later reprimand, and then her allowance of him back into the White House afterwards. Simply not possible. It is, no pun intended, the smoking gun in all this evidence.

Plausible indeed…but why would Mrs Lincoln assassinate her husband?

I believe Mary knew it was going to happen because of your said evidence and they fact that she chose the venue. She went into an asylum so she could not be questioned. Many people knew it was going to happen. The minister of agriculture Isaac Newton for example reported the (incident in full detail including the bullet entry ) to the White House just 20 minutes after the gun was fired, the gun had to be fired Lincoln got to by the doctors diagnosed and verbally said for newton to know the details. He then had to leave the fords theatre and the very stout man that he was he had to then travel 4 blocks to the White House enter the premises and report the diagnosis just 20 minutes after the gun shot. Not possible unless the assailant told him the details on the way to the White House. The real killer was Edwin Stanton’s niece who probably simply walked away from fords theatre with him.

Her assistant and future husband rode of and was reported by James Tanner to have headed north and it is said was tracked by Lafayette all the way to Harper’s ferry before being told to go south in a totally different direction by Stanton. The real killers husband to be lived in Kentucky accessible via Harper’s ferry all the way to the Ohio river.

All the real killer ( 19 year old Edwin Stanton’s niece) had to do was stop off at stantons house and jump on a train with Laura Keene who was free to just leave to go to Kentucky.laura Keene was involved. By allowing them access to the box below and standing in a location making sure nobody else could see in the box below the president.

Laura Keene was involved with the assassination and was herself of British royalty . She was paid by being given a house in acushnet by the family of Hannibal Hamlin who would but a late government directed change have been the Vice President and subsequent ly president on Lincoln’s demise. Laura Keene’s neighbours were the Roosevelt family which was visited by the child who would later be the a president.

Edwin Stanton’s family was related by marriage to Charles guitteau who assassinated James Garfield. With Lincoln’s son close by and the same son who who put Mary Lincoln into the asylum. Abraham Lincoln before becoming president was a debt collector for Benjamin tappan jr a son of a banker of the same name in New York .that tappan was married to Edwin Stanton’s sister oella and that tappans wife was intermarried with the guitteau .

This is how relationships were hidden Edwin Stanton was related to the wife of dr Mudd and the wife of Garrett of Garrett’s farm. It was the wife of tappan who was related to the guitteau familly.

This is how history was hidden. Stress Mudd and nobody looks at mudds wife’s maiden name .

Stress Garrett and nobody analyses his wife’s maiden name Holloway Edwin Stanton was related to Charles Dana and was related to Joseph holt. John Minchin Lloyd whose testimony pretty much got Mary surratt hung was related through his wife’s maiden name offutt . Threaten the family and anyone will say exactly what they are told to say. Stanton knew every witness he was either employing them like weissman or moreover was related to them and could reward them with thousands of dollars. If incompliant like dr Mudd then they were imprisoned to keep them from being held. Dr Mudd on his release was to old to fight ant knew what would happen to him if he tried afterall the totally innocent surratt was hung. Ned strangler released ant the same time worked after on a farm with dr Mudd . Ned on the occasion of his death left a note saying that booth had no issue with Abraham Lincoln whatsoever.

Although I’m an agnostic when it comes to information i can’t personally verify with some research of my own i must say i was Fascinated and riveted McGowan had a style that has few rivals. His connecting of the odd pieces of history, family lineage and stubborn facts eye opening indeed. Thank you to his daughter for allowing me to read his work. You have done a great honor to your father and his legacy.

Just a thought, is there any significance to the name of this website. It can’t be overlooked that it could be abbreviated CIA. I recall that McGowan made cynical reference to a shady organization with the same letters in his LC series or was it theserial killer series? His untimely death saddens me. If there is an after life, I’m sure he is no doubt holding court with Anthony Sutton, Danny Caselaro and Gary Webb. Dave McGowan’s body of work demonstrates to humanity what an investigative reporter can do.

Again thanks.

Yes, the word play in the website name is an intentional joke on Dad’s part.

JFK also died on 11/22. Hmm.

has anybody noticed that on the revised wanted poster of surratt/booth/herold the photo used of surratt shows him in his papal uniform?

No surprise. Surratt, who had nothing to do with Lincoln’s murder, was a Confederate functionary known to the Union military, which, because of Stanton, allowed him passage through the North, from the Quebec hotel where both North and South businessmen conducted under-the-table business, back to D.C. Surratt absconded, via the help of Jesuit clergy, through Quebec to the Vatican, where he served in the papal guard until discovered. This seemingly bizarre connection should tell you about the European powers that wanted Lincoln dead, if, for nothing else, his desire to end the war as soon as possible, costing many in his own cabinet and military, as well as Southern businessmen, huge profits. It’s always about the money, not bullshit claims about freedom and liberty for we the little people.

Wow…the whole tale reeks of lies and collusion. Much like the demise of Osama bin Laden…pieces just don’t connect!!!

It is also the same picture of Herald the photographer took where his hands were shackled.

I admire your father writing and research so much. I think it would be a wonderful idea if an animation could be made depicting the conflicting testimony of each of the witnesses at the key locations of the events of April 1865. Something like this could be done in this day and age with all our technology. Why anyone with this technology hasn’t done it is perhaps to answer the question.

Thank you for posting this fascinating account.

quite sorry to hear of mr. McGowan’s passing.

I’ve really enjoyed reading his stuff and am sad there won’t be more.

thanks for everything.

I went to the Smithsonian in DC two years ago, and saw the sorry excuse they had for the Civil War.

“The Civil War was about Slavery” was the greeting sign on the door.

Eventually I saw the small display on JW Booth – I shouted “My hero!” A hush fell upon the room, my wife chided me, – I laughed. Lincoln is my distant first cousin, and the only president to kill 8% of “his” countrymen for a tax increase and destruction of the constitution- not for slavery.

I actually hope there was a “conspiracy” to take him out. This would then predate JFK.

after reading When In the Course of Human Events, i agree with you completely. Lincoln was a mass murdering war criminal. his death was richly deserved. had it happened sooner, it is possible that he would have only been able to murder 4% of population.

the war was not about slavery – it was all about empire and taxes.

Mr. Fehrmann, I suspect you know ALL TOO WELL that freemason and Confederate General Albert Pike was the man responsible for initiating the Civil War. The next time you are in WDC, go see Pike’s statue in Judiciary Square.

Expressing doubt about the fact that Bin Laden was killed and that his body buried at sea will tend to make many people question everything else you say. Bin Laden’s body was only buried at sea after it was taken to Afghanistan’s and its identify confirmed with DNA testing. Numerous photos were taken and dozens of people have stated that they’ve seen them. But releasing those photos would only inflame much of the Muslim world and would make him more of martyr than he already is. I suggest you remove the statements that question Bin Laden’s death.

Censoring my late father’s work would be against the spirit in which this website was created, so that will not be happening.

Well then, Mike, you must also believe that one about the 19 crappy amateur pilots that defeated all U.S. intelligence and military apparatuses, as well as the magically collapsing buildings, on September 11, 2001.

i question bin laden’s death during the obama administration to the point of not believing it all – it was pure theater. bin laden was tim osman who died in december 2001 in a us hospital in the middle east.

You, know, Mike, I was with you on the F-bomb thing, but this is just unreasonable. Showing pictures would enflame the muslim world? What about continued military occupation in the muslim world? What about creating ISIS and fomenting war in Syria? How about facilitating the murder of Yemenis by providing personnel and material support to the Saudis? Does this not enflame the muslim world? No, I’m glad they aren’t censoring the Bin Laden claims, and maybe you should get another hobby.

As a Muslim, I can tell you that we’re already well aware of the games being played. We wouldn’t have batted an eye over “his body” Tim Osman was a CIA asset. Sounds like you need to have a lot of mindset shifts regarding how the world really works and who your really enemies are. Clearly you didn’t really understand Mr. McGowan’s work. I hope you figure things out before your overlords yank the rug from under you while you slumber in your delusion.

“Well then, Mike, you must also believe that one about the 19 crappy amateur pilots that defeated all U.S. intelligence and military apparatuses, as well as the magically collapsing buildings, on September 11, 2001.”

Yes, I certainly do believe those things, partly because the bad guys have proudly *admitted* that they were the ones who ordered and planned the 9/11 attacks. There was nothing magical about the collapse of the Twin Towers and WTC 7–their collapse has been thoroughly and definitively explained, starting with the articles in Popular Mechanics. Find me a single genuine scientist who thinks otherwise (again, a *genuine* scientist). I suppose you also believe that a missile, and not an airliner, hit the Pentagon on 9/11? I live in Northern Virginia and have friends who saw the wreckage of the airliner in the Pentagon. Dozens of people who were driving near the Pentagon that day saw the airliner flying unusually low and heading straight toward the Pentagon.

It is very unfortunate that Mr. McGowan’s important and informative research on the Lincoln assassination is tainted by the advancement of the untenable and discredited 9/11 conspiracy theories. I run a heavily trafficked website on the Civil War, but I will not link to Mr. McGowan’s articles as long as any of them contain comments that endorse the 9/11 conspiracy theories or that question the fact that Bin Laden was killed in the Abbottabad raid.

I am certainly open to the possibility of conspiracy in certain cases when the conspiracy theory is rational and is supported by credible evidence, such as the JFK assassination and the MLK assassination (see, for example, my JFK assassination website on my homepage given below). But the 9/11 conspiracy theories and the theory that Bin Laden was not killed at Abbottabad are not only irrational and illogical but are not supported by a shred of credible evidence. Many of the same few people who peddle the 9/11 conspiracy theories also peddle the absurd claim that the moon landings were faked.

“Many of the same few people who peddle the 9/11 conspiracy theories also peddle the absurd claim that the moon landings were faked.”

Funny you should say that. On this site. Where http://centerforaninformedamerica.com/moondoggie-1/ and the rest of it does such a fine job of revealing exactly that lunar fakery.

The Gutenberg press cost the established Church its control of the civic narrative. The Internet, in turn, has cost the modern political establishment its control of the civic narrative.

It’s a bit of a chore, sifting through the misdirection, bluster, and outright lies, but it’s reached the point where the intensity of the scorn (e.g., “untenable and discredited”, “not supported by a shred of credible evidence”, “absurd” claims, and the like) is more a beacon lighting the inquirer’s way, than a deterrent.

In short, the louder they shout, “Nothing to see here, folks!” the more there is to see there.

Thank you, Mike…

I live in the middle of Puerto Rico, my own Hur. Maria, and didn’t want to but read your reply, and when I read that the article in Popular Mechanics definitively explained, I burst into laughter for the first time in so long that I must thank you. God knows I needed it.

It’s sad that Dave is no longer with us to respond to such ridiculous comments. I guess someone hasn’t bothered to read the rest of the content on this site.

Why not just link to this series with a disclaimer that McGowan was a conspiracy theorist (to be fair, I’d call him an anti-coincidence theorist here) about a bevy of other historical events, such as 9/11 (forget the physical theories, the circumstantial case for LIHOP is compelling enough), JFK (similarly, the ballistic evidence is superfluous compared to the impossibly spooky network of improbable relationships), Osama Bin Laden (I agree that there was almost certainly no conspiracy, but McGowan’s point is that we are forced to trust the testimony of a little clique of secretive operators as proof), satanism and mind control and blackmail (he’s way less wrong than you’d hope, we really do live in a demented, gruesomely corrupt world), and the Boston Marathon bombings (about which he was way, way, way off the rails).

oh yeah – popular mechanics does it for me – NOT.

here are some architects who refute the idiotic 9/11 pan-cake theory and other absurd explanations for the collapse of wtc-7.

oh yeah – popular mechanics does it for me – NOT.

here are some architects who refute the idiotic 9/11 pan-cake theory and other absurd explanations for the collapse of wtc-7.

http://ine.uaf.edu/wtc7

(repeat – i forgot the link)

yep – sorry the moon landings were faked – 100%. the moon is a light source – there is nothing solid about it. a fly could not land on it.

anyone wanting to see a good documentary on the moon landing hoax should watch A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Moon

Careful, Mike, you’re glowing.

WTC 7 collapse has not been explained. A fifty story steel structure that was not hit by a plane just collapses? The first time in history? British media also reported the collapse before the actual collapse. The only explanation is the whole attack was scripted and the Brits got a script page early. They don’t have ESP. Wake up people. Google it!

WTC 7 collapsed in empathy for the other two.

A VERY thought provoking, well written narrative and excellent research done by Dave McGowan, as always!

R.I.P. Dear Soul! You are missed!

A most excellent series of articles, and my compliments to Mr. McGowan.

I wrote a book years ago about Lincoln and spent a lot of time on his assassination, but this has explained so much more than I was ever able to, despite visiting D.C. and seeing Ford’s Theater and the boardinghouse where Lincoln died.

I was also much impressed that Mr. McGowan connected the dots to expose Cheri Blair as a Booth. Very interesting!

Hi-it was fairly well known here in England that Cherie Booth Blair was a descendant of the same family as John Wilkes Booth. Her dad was a well known actor in Britain, Tony Booth. He was famously very outspoken about his left wing political views. Booth was one of the stars of BBC comedy series Till Death Us Do Part – playing the mouthy Scouse lad who constantly argued with his comically stupid bigoted East Ender father in law. Who was actually played brilliantly by an excellent Jewish actor – whose own politics couldn’t have been further from those of his Right Wing on screen character. Till Death scripts were toned down a lot when the show went to the US and became All In the Family.

The Booths are a very interesting clan. The more I read about them, the more I get drawn in.

Mike Griffith I guess Architects & Engineers for the truth about 9/11 don’t cut it as knowledgeable people in your mind. Obviously you haven’t read most of Dave’s brilliant work. I would say if you don’t like it then don’t read it but don’t be so arrogant and asked for it to be changed LOL.

There methods have not varied much over time. Just a little slicker, but not much. ” Horrible crisis actors” with their own goofy scripts as is the case with the Seward attack and other “fake” witnesses. News of the assassination sent out ahead of the assassination (Building 7). Infrastructure failures such as gaslights turned off and the telegraph down (security cameras not working as in many “events”). Stand down at the bridge (stand down of police and military during events).

A gripping yarn, easily cut by Occam’s razor? MR.McGOWAN employs an engaging style to propose many fascinating questions, but few answers. Time obscures all, but does not heal all.

Alissa, thank you for preserving your dad’s excellent work. I’ve never run across anything like it.

Honestly amazed at what I’ve run across here and in Programmed to Kill. I approach these things from a skeptical point of view, and keep that skepticism for a while… but eventually the overwhelming weight of evidence provided crushes that skepticism. Incredible work.

Interesting work, yet not complete. John Wilkes Booth did NOT shoot Lincoln. He was Mary Todd Lincoln’s drug dealer, and was part of a plan to kidnap the President, lock him up on an offshore opium ship, get him addicted to opium, and then release him in rags on the streets of DC.

Mary Todd Lincoln and the President were having serious marital problems with both of them having had extramarital affairs, and Mary was very angry with her husband.

She shot her husband!

John Wilkes was NEVER caught; and everyone who knew the truth was eager to cover up that

truth… Can you imagine the international shame America would have to endure if everyone knew that our President’s wife had shot her husband? Further, that single shot pistol was what she carried with her for personal protection.

BTW, the “Deep State” of that time was deeply involved in creating the ‘Civil War’, and in all that took place after Lincoln’s death. Many of the ‘authorities’ including Generals, prosecutor’s. and cabinet members were working for what we call today the Deep State or the Cabal.

Mary Lincoln’s aunt married deringer that made the gun. It was however another relation that did the shooting.

I stayed up all night reading this. I thank you for making this information available to everyone. I had never thought about Lincoln’s assasination being covered up before reading this. It just never occured to me. We are fed bullshit “history” beginning at a very young age and have to really look for the facts to find the truth.

To the fellow who cited Popular Mechanics; that’s Hearst media. Need I say more?

You have to assume everything is a lie for example did you know that Lord Mayors in england we’re appointed by royalty. John Wilkes Lord Mayor of england was the the the great uncle of John Wilkes booth and fervently pro union against he king.

Did you know the Egerton the wife of Abraham enloe the disputed parent of Abraham Lincoln. She was the relation of scroop Egerton Lord Mayor of england too and enloe or enlow is a derivative of Henley who guess what , was a Lord Mayor of england.

So what you might say ! I certainly did , But , did you know that isom enlow a cousin of Abraham enlow was Lincoln’s neighbour in Kentucky and oversaw his childhood. Isom enlow married a lady named brooks who oversaw the birth of the man that was to be named Abraham Lincoln . That same wife (brooks ) also married the great uncle of Henry rathbone. She also married again and had the surname larue and was related directly to governor larue of Kentucky who was a relation of Mary Lincoln. As in America there was also a civil war in England.

That war concerned those loyal to the Scottish queen Mary and those loyal to her cousin queen Elizabeth 1st. Scroop Egerton was loyal to the English kings who incidentally had Mary queen of Scots and charles 1st both Scottish royals beheaded.

Just for further information Mary queen of Scots was the rightful heir to the thrown . The English parliament changed the law allowing Elizabeth the first who was an illegitimate descendant of Henry the Vlll

If Abraham Lincoln was actually enlow then he would have been related to a English appointed Lord Mayor. The chief deferral to Lincoln being Abraham enlow was John Calhoun also a relation of Edwin Stanton who incidentally was a descendant of governor cranston of Boston mass. Who in turn was a descendant of Princess Diana of england mother of the second in line to the thrown currently.

John Wilkes Lord Mayor was loyal to the Scottish and particularly John Barclay whose picture was the only picture ever hung on the wall of the White House when Lincoln lived there.

Elizabeth gurney who’s letters were found in Abraham Lincolns pocket was the wife of John gurney also loyal to William penn and John Barclay aforesaid.

So the question is was Abraham Lincoln the son of a Lord Mayor of england and subsequently appointed by the English. If so then the Scottish royalty were the enemies of that Lincoln.

One little additive is ( because I now know the bigger picture of the assassination ) there was another person a miss Mary Hayley she was doing extensive trade from New York and withe the familly of Foote who indeed were family of France’s Adelaide Miller the wife of William Seward the Secretary of State also claimed to have been attacked.

That Mary Hayley doing extensive international trade with quakers throughout the world and with the Foote relation and with indeed Frederick Seward. That Mary Hayley was no other than the sister of John Wilkes Lord Mayor of england and ancestor of John Wilkes Booth.

France’s Adelaide Seward had close relations with Elizabeth cady Stanton married to a relation of Edwin Stanton.

These family’s traded in new Albany New York with the livingstons descendants of Houston’s and the Rathbones .

I know enough now to rewrite history and indeed the so called bigger picture which does not involve John Wilkes Booth other than the fact that he was deliberately targeted because he was a relation of Lord Mayor John Wilkes.

History concentrate on the surnames of the individualas when the middle names or married names are the important ones.

Did you know that Edwin Stanton was related to dr mudds wife and on the Lincoln name side Lincoln’s claimed uncle mordecai Lincoln was married to a cousin of dr Mudd.

Did you know that the Holloway wife of the occupant Garret of Garrett’s farm was a relation to Edwin Stanton and the confederate family of Mary Lincoln.

The escape route claimed to be that of John Wilkes Booth is ‘on line’taken by others and included the and indeed they met dr Mudd and John surratt , these people (not John Wilkes booth were smuggling goods north to south for profit and they were caught and their experiences and route reported to a general wilder to whom was responsible to Edwin Stanton . No action was taken against the smugglers but their route was used to incriminate John Wilkes Booth. Using dr Mudd and the Garrett’s both related to Edwin Stanton.

I know of the whole bigger picture and those interrelations concerned all of which were Stanton related.

Agree with Dennis. Lincoln’s cotton tariffs gave New England textile mills protection against UK mills. This made him an enemy on both sides of the Atlantic. The UK gave the CSA much naval support. Similar to Trump’s Chinese tariffs in Oct. 2019 and what’s followed since.

Fascinating read. Incredible research. Having been down the research rabbit hole I understand. Make no mistake if you tread where you shouldn’t there are consequences and suicide/unexplained death happens. I avoided that by backing off when threatened. Your father was much braver than I. Thanks for keeping your father’s research alive.

This is a large step in the process of enlightening mankind. Thank You for giving it to us. It’s really great work.

The bigger picture is huge. Did you know for example that Edwin Stanton was related to Charles guitteau

Spectacular research by our dearly departed Mr Dave McGowan. I’m a little sorry to be at the end of the series and much more sorry we don’t have his wit and sarcasm to see us through the Covid nonsense today.

Dave did a newsletter back in 2003, #39 about Jesse James, which is a nice follow-on to this series.

https://centerforaninformedamerica.com/newsletter-39/

Thank you Alissa for keeping your fathers work available for all of us to see.

All the best,

Steve D

Jesse James was related to the queen of England haha and so was Edwin stanton , Laura Keene, and George purnell fisher who knew John surratt was innocent because it was his relation that held up Edwin Stanton’s niece from the box below to fire the deringer that killed lincoln

What I really don’t like about this treatment is that he does not offer his own hypothesis.

Yes, I am convinced, that John Wilkes Booth was not the man in the barn. It may even be the case that John Wilkes Booth, for all the reasons given, was not the assassin at all. That leaves one of the members of Lincoln’s party in the box in Ford’s theater. so I point also to the likelihood of this explanation as the derringer (especially a SINGLE-SHOT derringer!) was universally a personal defensive weapon, nothing more. Derringer’s were often called “muff guns” because women carried them in the “muffs” into which they inserted their hands in winter to keep them warm when out on the town. The author’s excellent analysis of the problems with the “official history” demands, however, a cogent wrap-up.

John Wilkes booth was not there and the real killer was not one of the other three.

The real killer was Edwin Stanton’s niece and her husband to be.

Very good but McGowan makes a big mistake thinking that people wouldn’t risk their life for the confederacy or that their love for it wasn’t real. I think this is because he doesn’t see the upwards pressure from the radical republicans pushing the unionists to civil war. If the leadership of the unionists had it their way, the confederacy would have won. The administration of Buchanan and the leadership of the “unionists” prove this.

All these comments and to some extent McGowan’s writings suggest that Lincoln died from injuries suffered on April 14, 1865.

Did he?

There is another Elissa , Alissa ! She was the granddaughter of the aunt by marriage to Mary Lincoln’s fav niece. So had sufficient knowledge of their attendance at fords theatre which to all intents and purposes was a late decision to attend.

That aunt was Ann Houston, Ann’s nephew William fisher, was in attendance with his wife to be who standing on the shoulders of William, reached out through a hatch in the floor of the presidents box , rested her hand and gun against the chair provided by another relation John Thompson ford. That bullet entering low behind the left ear of Lincoln to behind his right eye.

Does anyone have any book suggestions that explore the “deep state” roots of the civil war and the real motives? This series by Mcgowan blew my mind and I would love to look more into the deep state forces of the time.

Andrew, Regarding your question, “Does anyone have any book suggestions that explore the “deep state” roots of the civil war and the real motives?” I suggest you research ALL you can about who was freemason and Confederate General Albert Pike. Following the murder of my Christian mother by my freemason relatives in March 2012, I started researching all I could about masonry to discover why my cousins could do something so heinous to one of their own relatives? During my research, I also learned that my relatives are Jewish, a family secret hidden from the small Christian branch of the family tree (of which I am one) for over 100 years. Thereafter, I was blocked from looking further at my family tree on Ancestry.com by my cousins. Look up what is the meaning of “crypto-jew.” I would be remiss if I didn’t add that I also discovered my 2nd stepfather had been the major-domo Illuminati who ran the state of Indiana while he was alive, as had his relatives before him. [Indiana is in fact named for the goddess, Diana, with the sexual inuendo “in” hence, “in-Diana.”]

Follows is a list of books I found most helpful listed for the most part in the chronological order I read them, which helped immensely for the first book built a foundation the later books are built on.

1. The Grandees: America’s Sephardic Elite by Stephen Birmingham (get the 1971, not 1986, edition)

2. When Scotland Was Jewish by Elizabeth Caldwell Hirschman [Don’t look now, but the entire U.K. is mostly Jewish.]

3. Jews & Moslems in Colonial British America by Elizabeth Caldwell Hirschman

4. The Synagogue of Satan by Andrew Carrington Hitchcock

5. Holy Serpent of the Jews by Texe Marrs

6-8. Scarlet and the Beast by John Daniel, Volumes 1, 2 and 3

9. The King James Bible Authorized Version You MUST be a born-again Christian to understand the bible [1 Corinthians 2:14, “But the natural man receiveth not the things of the Spirit of God: for they are foolishness unto him: neither can he know them, because they are spiritually discerned.] However, I will state for the record that 1. There are verses throughout the bible refuting the “secret societies” of which Freemasonry is the best known. See Isaiah 5:20-24, for example; and 2. The mason publishers of the bible have deleted the word OBELISK throughout the bible, replacing it with the word IMAGE so that modern men cannot make the connection between ancient Babylonian Pharisaism and present day Freemasonry. [Compare the bible verse Jeremiah 43:13 in the KJV: “He shall break also the images of Bethshemesh, that is in the land of Egypt; and the houses of the gods of the Egyptians shall he burn with fire.” to Jeremiah 43:13 in the Revised Standard Version bible: “He shall break the obelisks of Heliop’olis which is in the land of Egypt; and the temples of the gods of Egypt he shall burn with fire.'”

Lastly, know that Babylonian Pharisaism = Judaism = Freemasonry – all three being the same religion yet having different names throughout history.

10. Watch/listen to as many videos by William M. Cooper as you can on YT among other websites.

11. Listen to the audio tapes by former Illuminati witch, John Todd. There are 14 tapes total on the ‘net.

Should you have any questions, you can contact me at; CHoffmanJedi@yahoo.com

PS: It’s my understanding George Lucas created the word “Jedi” by taking the first two letters of the words Jesus and disciple making Je+di, which is then NOT New Age for me but rather an appropriate moniker.

Kind regards, Cynthia

Dr. Samuel Mudd’s wife’s name was Sarah Frances DYER Mudd. Her maiden name was Dyer, and old Southern Maryland family name.

If these are indeed the facts, then there’s no doubt that this was not carried out by a lone gunman named John W. Booth

There were too many convenient failings on the part of too many people. The suspicious behaviors of Mary Lincoln and General Grant, the guard on the Navy Yard Bridge, the malfunction of the telegraph system, the policeman who was supposed to be guarding Lincoln’s safety, and all the other anomalies point to a conspiracy in which many colluded.

What has been omitted from these articles is the fact that Lincoln was printing his own money, in defiance of the international bankers, Rothschild’s and Morgans, who wanted to loan the government money with interest to get the country back on its feet.

Thank you for Mr.

Mcgowan’s work to be out in the public domain.

Would it be possible to obtain a bibliography to the Lincoln and Wagging the Moondoggie?

I admit, after looking throughout the web(sooo NOT Google) I’m having a tough time tracking sources.

There is so much history we’ve been taught that is misleading and someday I would love to put together a compilation of the history that’s been marginalized.

Such as

Lincoln

Moon

Michael King

LBJ

Hitler & Prescott

The Mandelas

WW1 & 2

McCarthy (Was Right)

Rosa Parks

Oakland City

etc.

What we think we know, is a smidgen of truth, mixed with misdirectionS, and two tons of blatant lies!

I’m so disappointed that I could have cared less about history until 9|11 & building 3.

Since 2010 I’ve been digging! What a journey of barely scratching the surface of history.

If you are able to provide this info or if anyone has history information that is contrary to the “know” narrative, you are more than welcome to email me at dhodson66@gmail.com.

Most appreciated

With a smile,

Dawn

Does anyone know if the “conspirators@ who were hanged were visible and identified (hoodless) before hanging? Just wondering if those particular ppl were hanged or just regular prisoners in their place.

Fantastic series and this is the second reading I’ve given it. I so appreciate you preserving your dad’s incredibly excellent work, Alissa. Thank you.

As he says, the same b.s. continues today. I so wished that Dave had lived to take down Covid19, the Ukraine war, January 6, the 2020 “election,” etc.