According to the official story, Powell came calling at the Seward home the night of April 14 under the guise of delivering medicine for the ailing William Seward. He was greeted by houseboy Bell, whom he allegedly brushed past while insisting that he was to hand-deliver the medications. Powell was then confronted at the top of the stairs by Frederick Seward, who insisted that Powell leave the package with him and not bother the sleeping Secretary of State. Powell then turned to leave, took a few steps down the stairs, and then pulled a gun and attempted to shoot Frederick. When the gun failed to fire, he supposedly bum-rushed Frederick and brutally beat him nearly to death.

According to Bill O’Reilly’s overwrought version of events, “The two men grapple as Powell leaps up onto the landing and then uses the butt of his gun to pistol-whip Frederick. Finally, Frederick Seward is knocked unconscious. His body makes a horrible thud as he collapses to the floor, his skull shattered in two places, gray matter trickling out through the gashes, blood streaming down his face.”

During that encounter, Fanny Seward supposedly looked out from her father’s room and in doing so conveniently gave away William Seward’s location. So after incapacitating Frederick, Powell next burst into William Seward’s room and encountered George Robinson, whom he grappled with before beginning to brutally slash away at Seward. At that time, Augustus Seward, who had been awakened by all the commotion, allegedly entered the room and began grappling with Powell. Powell though got the best of him as well and then bolted out of the room and down the stairs. In most versions of the story, there is no further mention of Fanny Seward, who was supposedly in her father’s room throughout the ordeal.

On his way out of the house, Powell allegedly encountered Hansell, who had just arrived at the home. Hansell was supposedly brutally attacked and left for dead just inside the entrance to the home. Powell then exited the residence and rode off into the night. And that, in a nutshell, is the official story of how one man was allegedly able to leave at least five people mortally wounded while walking away without a scratch.

Frederick Seward, showing the severe scarring from his alleged beating

The witnesses who appeared before the military tribunal, however, had a very hard time keeping the details of that story straight. Here is a portion of Robinson’s testimony, delivered on May 19, 1865: “The first I saw of [Powell] I heard a scuffling in the hall; I opened the door to see what the trouble was; as I opened the door he stood close up to it; as soon as it was opened wide enough he struck me and knocked me partially down and then rushed up to the bed of Mr. Seward, struck him and maimed him; as soon as I could get on my feet I endeavored to haul him off the bed and he turned on me; in the scuffle there was a man come into the room who clutched him; between the two of us we got him to the door, or by the door, when he clinched his hand around my neck, knocked me down, broke away from the other man and rushed down stairs.”

Amazingly enough, neither the prosecutors nor the defense attorneys bothered to ask him who this other mystery man was. Clearly though it wasn’t Augustus Seward, who Robinson, a household servant, would certainly have recognized. When asked specifically whether he saw Powell’s alleged “encounter with Major Seward,” Robinson replied that he “did not see that.” When asked about Frederick Seward, he responded as follows: “I did not see Mr. Frederick Seward around at all.” So George Robinson did not see the guy who was supposedly lying in a bloody heap just outside the door to William Seward’s room. He also didn’t see the guy who supposedly assisted him with trying to subdue Powell. And he didn’t see, or at least didn’t mention, Fanny Seward. But he did see some mysterious, unidentified stranger.

When later asked, “Where was [Frederick] when [Powell] came out [of Seward’s room]?”, his unexpected response was: “The first I saw of Mr. Frederick was in the room standing up; he had come inside the door.” So it appears that the guy who was lying near death somehow magically got up and strolled into the room, hopefully after pushing the gray matter back into his shattered skull.

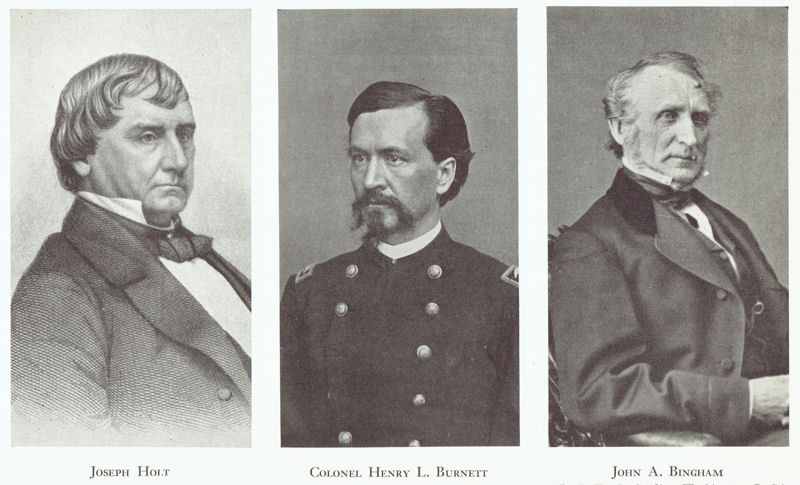

The prosecution team: one of Burnett’s duties was to oversee the rewriting of the trial transcript to remove various contradictions and inconsistencies

Robinson also told the court that he never heard Powell utter a sound throughout the ordeal. Judge Advocate Holt, sounding a bit incredulous and clearly not getting the answers he wanted, asked the witness this question: “You say that this man, during the whole of this bloody work, made no remark at all; that he said nothing?” Robinson responded with: “I did not hear him make any remark.”

Let’s now listen in to some of Augustus Seward’s testimony, because this is where it really gets interesting: “I retired to bed about 7 o’clock on the night of the 14th, with the understanding that I would be called at 11 o’clock, to sit up with my father; I very shortly fell asleep, and so remained until wakened by the screams of my sister; I jumped out of bed and ran into my father’s room in my shirt and drawers; the gas in the room had been shut down rather low, and I saw what appeared to be two men, one trying to hold the other; my first impression was that my father had become delirious, and that the nurse was trying to hold him. I went up and took hold of him, but saw at once from his size and the struggle that it was not my father; it then struck me that the nurse had become delirious and was striking about the room at random; knowing the delicate state of my father’s health, I endeavored to shove the person I had hold of to the door, with the intention of putting him out of his room; while I was pushing him he struck me five or six times over the head with whatever he had in his left hand; I supposed it at the time to be a bottle or decanter he had seized from the table; during this time he repeated with an intensely strong voice-‘I am mad, I am mad;’ on reaching the hall he gave a sudden turn and breaking away from me, disappeared down stairs.”

You got all that straight? Augustus first mistook Powell – a strapping, physically fit, 20-year-old man – for his frail, 63-year-old, bedridden father. Following that, he next mistook Powell, a decidedly fair-skinned Caucasian lad, for his father’s black nurse. He also completely failed to notice that Robinson was right alongside him grappling with Powell. And he failed to notice that his sister was in the room. And he distinctly heard Powell loudly proclaiming himself to be mad, even though Robinson, also in the room, didn’t hear Powell utter a word.

Augustus was also asked about his brother Frederick, to which he responded: “I never saw anything of my brother the whole time.” In other words, he didn’t notice that he had to practically step over his brother’s prone, bloody body to get to his father’s room. And he apparently wasn’t paying attention when Frederick stood up and walked into that room.

It’s Booth’s photograph – just not the right Booth

Coupled with the conflicting testimony of Seward and Robinson, there is the enduring mystery surrounding Emerick Hansell. According to the official version of events, Hansell was left lying nearly lifeless just inside the front door of the home. But Dr. T.S. Verdi, the Seward family physician, testified that he “found Mr. Hansell, a messenger of the State Department, lying on a bed, wounded by a cut in the side some two and a half inches deep.” He went on to say that that bed was in a third-floor bedroom! Needless to say, no explanation was offered as to how and why Hansell could have ended up there. On that particular night, apparently, it was not uncommon for mortally wounded guys to get up all by themselves and wander around the Seward manor.

It seems pretty obvious that of all the witnesses to testify before the tribunal, none were more important to securing convictions than those who claimed to have witnessed the crimes actually being committed. It seems more than a bit odd then that the state bypassed both the First Lady and a senator’s daughter in favor of an otherwise obscure future murderer named Henry Rathbone, who was clearly reading from a script written by unseen others. And it also seems more than a little odd that the state also left no fewer than five members of the Seward household and a State Department courier sitting on the sidelines in favor of two lowly household servants and a member of the Seward family who, by all accounts other than his own, wasn’t even in the home that night.

It is on the shoulders of those four men – Augustus Seward, William Bell, George Robinson, and Henry Rathbone, all of whom are all but forgotten and all of whom presented obviously perjured testimony – that the official story of what happened on the evening of April 14, 1865 in the presidential box at Ford’s Theater and at the Seward home has now rested for 149 years.

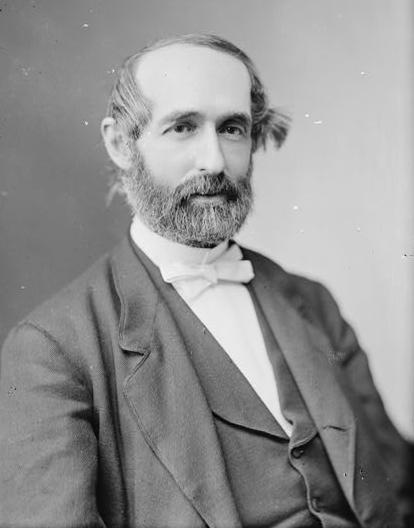

Defense attorney William Doster

As for Bell, his testimony was problematic as well: “When [Powell] came he rang the bell and I went to the door, and this man came in; he had a little package in his hand, and said it was medicine from Dr. Verdi; he said he was sent by Dr. Verdi with particular directions how he was to take the medicine, and he said he must go up; I told him he could not go up … he said that would not do, and I started to go up, and finding he would go up I started past him and went up the stairs before him … I noticed that his step was very heavy, and I asked him not to walk so heavy, he would disturb Mr. Seward; he met Mr. Frederick Seward on the steps outside the door, and had some conversation with him in the hall.”

After describing a lengthy argument between Powell and Frederick Seward, Bell testified that Powell “started toward the steps as if to go down, and I started to go down before him; I had gone about three steps, and turned around, saying ‘don’t walk so heavy;’ by the time I had turned round he jumped back and struck Mr. Frederick Seward, and by the time I had turned clear around, Mr. Frederick Seward had fallen, and thrown up his hands, then I ran downstairs and called ‘murder;’ I went to the front door and cried murder; then I ran down to General Auger’s headquarters at the corner.”

Finding no one there, Bell ran back to the house in time to see Powell run out and get on his horse. Asked if he saw “with what [Powell] struck Mr. Fred. Seward,” Bell responded that “it appeared to be round and wound with velvet; I took it to be a knife afterwards.” For the record, it was actually supposed to be a gun.

Probably seeking to avoid perjuring himself too brazenly, Bell adopted the “I didn’t see nothing” approach. Powell, acting with superhuman strength and speed, managed to get to and subdue Frederick Seward before Bell could even turn around – after which Bell left the house, missing the rest of the carnage and returning just in time to witness Powell’s escape.

One wonders though how Emerick Hansell, the Steven Parent of this story (look it up), somehow managed to not see or hear Bell’s frantic flight and shouts of “murder” as he approached the Seward house that night. And why no patrols were near enough to respond to his cries. And exactly how long it took William Bell to turn “clear around.” In any event, we know that we can rule Bell out as being the mystery man who assisted George Robinson.

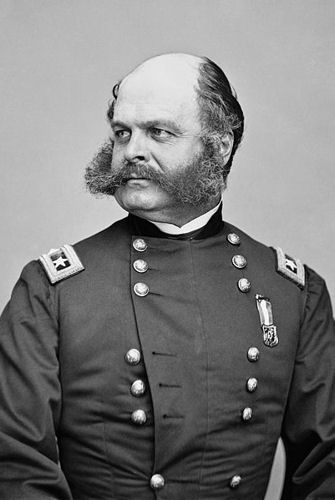

Union General Ambrose Burnside

Amazingly enough, after nearly a century-and-a-half, no one has ever seriously questioned the official narrative of what exactly happened that night. There have been just a relative handful of books written that question various aspects of the assassination, such as whether there were other, unseen conspirators, and whether John Wilkes Booth really was gunned down at Garrett’s barn, but even the authors of those books have unquestioningly accepted that what the state says went down in that presidential box and in the Seward home really did happen.

But why? On what basis should we blindly accept those aspects of the official story? Why should we believe a guy who when called upon three times to tell his story under oath, told that story in the exact same words all three times? And why should we believe two guys who supposedly stood side-by-side to fight off an intruder without either noticing the other’s presence? And who both somehow failed to notice the allegedly mortally wounded Frederick Seward lying right outside the door? And why should we believe a guy who absurdly claimed that he confused a young, physically fit Lewis Powell for his own invalid, aging father, and then claimed to have confused the very same Lewis Powell with the shorter, older, and much darker George Robinson?

How is it possible that no one has questioned any of that? Do I have to fucking do everything around here?

There were, needless to say, other irregularities in what passed for a trial, including the wholesale suppression of exculpatory evidence. And the introduction of brazenly manufactured evidence, like a supposed cipher letter, also introduced into evidence at John Surratt’s trial, that had allegedly been retrieved from a river but that clearly had never been in the water.

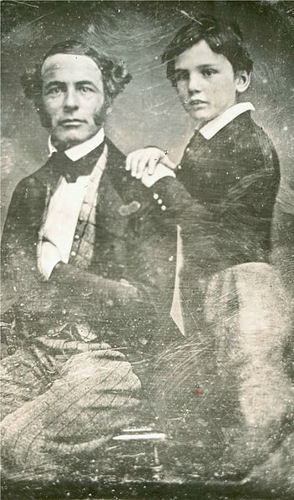

Confederate General Robert E. Lee, with son

To briefly recap then, all of the following were distinguishing characteristics of the ‘trial’ of the conspirators:

- The defendants were informed of the charges against them just 72 hours before the trial began, depriving them of the ability to put together an effective defense.

- The defendants, all civilians, were subjected to military justice.

- The defendants were denied their right to individual trials.

- The defendants were not allowed to speak in their own defense.

- The state willfully withheld the list of prosecution witnesses, denying the defendants their right to know the nature of the testimony they would be defending themselves against.

- The state freely introduced inflammatory, prejudicial testimony.

- The state made extensive use of witnesses testifying under assumed identities.

- The state made extensive use of paid witnesses.

- The defendants were prohibited from privately consulting with their attorneys.

- The state was not shy about suppressing exculpatory evidence.

- The state was also not shy about introducing manufactured evidence.

- The state allowed subpoenaed defense witnesses to ignore those subpoenas.

- Only a simple majority was required to convict, and only a 2/3 majority was required to impose the death penalty.

And yet, through seven weeks of the most extreme prosecutorial misconduct imaginable, the entire defense team raised only twelve objections. They should have raised that many just during the first hour of the first day of the proceedings. If not sooner.

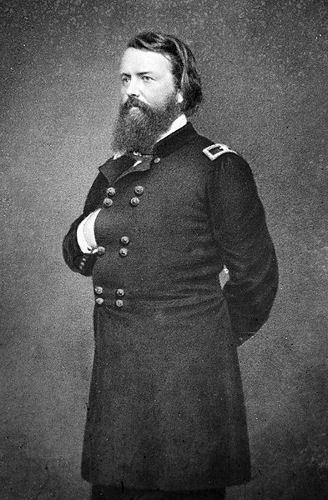

Union General John Pope

Union General John PopeOn June 29, 1865, the tribunal members met in a secret session to begin reviewing the evidence. It didn’t take them long to find all the defendants guilty. On July 5, President Johnson approved all the sentences handed down by the commissioners, including the death sentence for Mary Surratt. The very next day, four of the prisoners were informed that they would hang in less than 24 hours.

Mary Surratt’s spiritual advisers were denied access to her until they gave their assurances that they would not proclaim their belief in her innocence. Even then, they were allowed access only for a few hours. All of the prisoners were guarded very closely during their final hours by Thomas Eckert, Lafayette Baker, and a number of his thuggish detectives. Some of the gathered witnesses described the condemned prisoners as looking drugged as they were led to the gallows by Baker’s men.

More than a thousand soldiers ringed the prison walls to keep protestors at bay. Just after 1:30 PM on the afternoon of July 7, 1865, four soldiers kicked away the posts that were temporarily supporting the floor of the gallows and Mary Surratt, Lewis Thornton Powell, David Herold, and George Adzerodt fell to their deaths.

Meanwhile, military personnel escorted Dr. Samuel Mudd, Michael O’Laughlin, Ed Spangler, and Samuel Arnold to a remote, isolated, desolate facility known as Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas off the coast of Florida. Photos reveal that what was once undoubtedly a gorgeous tropical atoll had been converted by the US military into a veritable hell on Earth. The facility reportedly featured underground torture cells and dungeons. All four prisoners were held in solitary confinement in conditions so appalling that one of them, Michael O’Laughlin, was dead within two years.

Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas

And that, dear readers, is how ‘justice’ was meted out to the eight alleged accomplices of John Wilkes Booth.

FYI: There’s an error for a date listed in the paragraph below the photo of General John Pope. The paragraph begins: “On June 29, 1965, ….” The year should be 1865.

Thank you! Fixed!

The paragraph, late in this post, beneath the John Pope photo has a numerical typo and ought to begin “On June 29, 1865…” rather than 1965.

Thank you! Fixed!

If the prisoners sent to Florida were held in solitary confinement, how did Michael O’Laughlin contract and die from yellow fever, which is a highly contagious disease?

There would be guards, etc, right?

I mean, someone has to run the prison

Isn’t yellow fever also known as “Dengue” today? I believe it’s spread by mosquitoes.

My mentor in my Post-Doc, an MIT engineer with further doctorates in law and anthropology, sought these issues up to me back in the mid-nineties. His view was that Secretary of War Stanton, who always had despised Lincoln, had masterminded the whole thing wo that he would end up in the White House. He ran the trial so that the defendants could not speak and reveal his identity. On another matter, Marylanders in that day were not “northerners”. Maryland was a slave state, and Lincoln prevented secession ONLY by arresting and imprisoning the entire state legislature in Rhode Island for the duration of the war, and running the State by martial law. Baltimore itself was a hotbed of confederate sympathy, and the citizens there rioted and stoned Union troops passing through the city on a train prior to the war. The event is commemorated in Maryland’s post-civil war state anthem, Maryland my Maryland. The author seems actually befuddled on this point.

“Frederick Seward displaying the massive scaring after his alleged death beating” lol. Has there ever an author that has raised the lowest form of wit to such lofty and hilarious heights? God love and keep you Dave; there is rancid hidden mitt odour to your demise my gut keeps niggling me over, that I must compare to Stephen Knights. You lit up some very dark places that shows these “Good men made better” exactly what they were made better at. No wonder they require such sturdy aprons with such filth on their putrid hands, tongues and carbonised hearts; their souls had fled the minute they were hoodwinked.

By all mean proof read and edit the syntax “ has there ever BEEN” ; I am trying to write this on small phone screen since my computer died. Sorry for the omission.

But is there any doubt the Queens own Fraternities are the Frankist anathemas their history attests to? It is so far beyond implication I find it infuriating. I feel for the Chinese that suffered their drug dealing at the point of an assault rifle to now be patsies in the Crowns promised cull, Phillips death wish to return as a global human pathogen. Come on America, I weep for you sincerely and the promise of your decent folk.

I listened to the score by John Francis Brunner for the opening credits of the film “The Wild Country” last night and wept like a child at it beauty and the promise murdered by the same 1812 meddling enemy behind the Central banks that perpetrated all these assassinations upon any man honest enough to risk his life to give you a fair economy…. A grown 61 year old man and I howled like newborn. I fear we are lost to their global coven network now even America has foundered just like brave and gentlemanly J.J. Astor. An iceberg ….. yeh right…..

P.S. phalanx_warfare is punny multi layered cryptogram as I do many things with my fingers to the Glory of God and pleasant recreation. Some allied to Dave’s Socratic aspirations. Killing complete strangers during industrial crimes of mass murder, I have so far managed to avoid. As given the lying psychotic faction that infects us, I couldn’t guarantee I’d shoot the same direction as my brothers in arms.